On the Trail, Day Two: A Sample of Kentucky’s Bourbon Region

Day 2: Bardstown: Maker’s Mark and the Talbott Tavern

January 4, 2020

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] was the first one to get ready for what was going to be our principal day in Bourbon Country. I got up at about 6:15 a.m. (maybe a small annoyance to Gabby and my parents) and did my ritual of showering and shaving. However, I knew already I would take the longest – and so too did they.

The rest of my family was not all that far behind me, though, and we were all dressed and eager for breakfast by 8:15 a.m. The fluffy eggs and interesting apple-smoked sausage, along with my cup of strong coffee, was one of the more satisfying breakfasts I’ve had at any of the hotels we’ve stayed at. The lounge area itself was very inviting, and I appreciated that the manager was able to look up the carbohydrates on the sausage for me. He didn’t really have any obligation to do that.

We were on the road a little after 9 a.m. and made our way to Bardstown, which is essentially in the middle of Kentucky’s bourbon region. We got on Interstate 64 and then eventually onto U.S. 150 East (those more familiar with the area can probably fill in my gaps here), travelling on roads which sometimes cut through the limestone crust which jags out from the earth. This rock is what defines the distillation of Kentucky bourbon, because it filters out iron. This means you are left with a sweeter tasting mineral water. To put it simply, this base is indispensable, as well as unique.

Along the way, we passed several well-preserved homes on the side of the road, as well as a storage preserve used by Heaven Hill Distilleries. It was somewhat impressive to me to see a big rickhouse standing on top of a rolling hillside, and I wish I could’ve gotten a clearer picture of it. These frolicking juts are, more or less, the beginning of the foothills of the great Appalachian Mountains.

We arrived in Bardstown, and I was immediately struck by its colonial charm. It lives up to its 2012 honor of being recognized as the most beautiful small town in the country by Rand McNally and USA Today. The seat of Nelson County, Bardstown is Kentucky’s second-oldest community, having been inhabited since 1780 when the state was still a part of Virginia. It is also the home of Federal Hill, the mansion which inspired Stephen Foster to pen “My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!” Unfortunately, we were unable to go visit the state park which encompasses the property.

The center of the town’s historic district is the old courthouse built in 1892, and which is now Bardstown’s visitor’s center. However, it appeared that municipal functions are still carried out inside. A roundabout circles the building with streets coming in from each corner. From what we could see, Bardstown has undergone very little commercial development. There are at least 300 buildings which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the lot of them privately owned and kept. The oldest building is the Talbott Tavern, which was built in 1779 and still functions as an inn. We would eventually return to this landmark after our visit to Maker’s Mark.

But first, we thought it would be good to visit the Bardstown Bourbon Company before making our way to Loretto. To put it matter-of-factly, this distillery was not historic in the sense I was anticipating with Maker’s Mark or Bardstown. When we pulled up and saw the glass and modernist architecture, my dad said it looked “clean and sterile,” more about the business and not the craft. Still, it was a stop in my Kentucky Bourbon Trail “passport,” and, at the very least, Mom and I could “prime” ourselves by sharing a sample. We both were a little surprised by the whole thing.

A very friendly lady caught up with us as were we looking at a gallery displaying merchandise and some historic bottles of whiskey for sale. She told us that the Bardstown Bourbon Company began distilling in 2016, and that the building itself in its current form was only a few years old. Here’s the kicker: It is the seventh-largest distillery in the country. This is because it serves as a kind of middle man for distilling operations which are trying to establish themselves in the general market. It is not all that different from Midwest Grain Products (MGP) of Indiana in Lawrenceburg, which mainly sells its output to different bottlers (albeit with strict confidentiality agreements in place).

However, she made a convincing pitch that quickly got me on board with what they want to try and do in the bourbon industry. They work with 41 different mash bills which have been presented by these whiskey companies, and it is a collaboration between the two – though confidentiality is still key (if you really want to do the research, though, just look up the mash bills online). They take pride in professing to promote transparency with their operation, hence all of the windows.

If you think about it, these kinds of values are reflected by places like Wasser Brewing right here in Greencastle. It’s difficult to get started in the bourbon and beer businesses - let alone to continue on - because it is about producing a consistent product that people want to drink and continue to buy. I think that means we can appreciate what they are able to accomplish with the support of their respective communities. It’s one of those interesting connections that I think we can point to.

To be honest, it was their whiskey we sampled which sold us. We tried their Fusion Series #2, which has a mash bill of 12-year-old sourced Kentucky bourbon with BBC’s own stock. It was a smooth gulp with a little of the burn which characterizes whiskey in general. Mom and I both agreed it was better than the tastings at Michter’s. We made our approval evident enough that the lady said there was only one bottle left signed by master distiller Steve Nally – who is respectable enough to be in the Bourbon Hall of Fame – and head distiller Nick Smith. How could we say “No?” It now has a prominent place among my other booze, and I may never want to open it up.

I wish I snapped a picture of their extensive bourbon bar, which offers whiskey dating back to the mid-1800s. I would have loved to have asked the bartender about the price tags for those samples.

I was also amused by their social media counter, which automatically ticks when a new “like” or “follow” comes in. It’s another indication of how interwoven the industry can be with technology.

Finding ourselves out in the middle of nowhere, we finally arrived at Maker’s Mark at about 11:30 a.m., a little less than an hour before our tour of the distillery was to start. As soon as we were getting out of the car, we were greeted by a black Boxer and some mixed-breed. Because I had my door open, both of them leapt in and, for the most part, refused to get out without any prompting. They were a rather friendly duo, and we figured that they both were regular visitors to the property.

The Boxer looked as if it had a broken leg which never healed, and pranced with a pronounced swing. Both of them ran up to the visitor’s center and tried to jump on another couple. We were told later that they were not the normal “regulars” from nearby, and probably escaped from a yard.

We checked in and confirmed that Mom and I would be participating in a mixology class after our tour. We got our nametags and had about 45 minutes to explore the visitor’s center, which I surmise was the former home of the Samuels family, which started Maker’s Mark a fair while back in 1953.

The story of how Maker’s Mark came to be is rather interesting, and it began with Bill Samuels Sr. burning his family’s 170-year-old whiskey recipe. He wanted to separate from the harsh bite of “traditional” bourbon for a sweeter profile. To do so, he substituted rye with winter wheat, and the bourbon which makes Maker’s Mark a staple in any bar cart was created after a lot of testing.

It was his wife, Margie, who made Maker’s Mark iconic. The design of the bottle, the “maker’s mark,” the signature red wax - and the name itself - are because of her. They say Margie is the reason you buy your first bottle, and Bill Samuels is why you buy your second. I don’t think that’s just a marketing ploy; I believe it is an appropriate recognition. She was the first woman inducted into the Bourbon Hall of Fame, and Maker’s Mark remains the only bourbon named by a woman.

It turned out Samuels Sr. was a sixth-generation distiller, so the “IV” in their unique signifier is a misnomer. The star represents Star Hill Farm, which the Samuels family owned, and the “S,” of course, stands for “Samuels.” The company still recognizes that misnomer as being a historic one.

Some may note that Maker’s Mark doesn’t include an “e” in spelling “whiskey,” though it is, more or less, correct to do so here. The reason the company gives is that the Samuels honor their Scottish heritage. From what I could find, the usage of both spellings traces back to American and Irish brands wanting to distinguish themselves from Scotch whisky labels sometime in the 19th century.

When 12:20 p.m. came around – and after I had cleaned my hand where Whisky Jean, the distillery cat, scratched me while I tried to take a picture of her – we began our tour. Before we entered the main building, our tour guide, Brandy, pitched that Maker’s Mark uses a mash bill of 70-percent corn, 16-percent winter wheat and 14-percent malted barley. Bourbon in general, according to the Federal Standards of Identity for Distilled Spirits, must be made with at least 51-percent corn.

As is the sensible custom of other reputable distilleries, Maker’s Mark sources its grains from local farmers. This is another way through which the bourbon industry feeds into the regional economy.

After Brandy briefly explained the process by which the “whiskey” is received in its pre-aged state, we were led into where the mash is fermented in huge, wooden vats. The room was pungent with the smell of the yeast. When I dipped my finger into the ferment to sample it, all I basically tasted was corn. There was no sweetness or sourness, just corn. I pretty much expected this, though.

After we exited the fermentation house, we were shown into a small building which houses two Chandler & Price printing presses from the 1930s. They are still used to make the labels which go on each of the bottles. Two ladies prime the presses with the paper, and the tour guide said that 65,000 labels each can be printed in a single day. That’s not too shabby for a distillery that prides itself on being purposefully inefficient. I guess if the process isn’t broken, you do not screw it up.

I’ll certainly believe the tour guide when she says that those two ladies earn their weekends off.

We finally entered the main rick house where the whiskey is stored as it ages in charred oak barrels. I was surprised at first that it did not smell like “Heaven” as I thought I remembered it. It was a musty wooden structure that looked as if it had been there for centuries. It was permeated by the smell of the corn mash, though I don’t remember it being quite as strong as it was in fermentation.

I found it interesting that Maker’s Mark rotates its barrels between different spots in the rickhouses on a regular basis. The point of this is so that the aging can remain at a consistent level, and as such a consistency in flavor as a whole is achieved. They all really can’t just sit and collect dust.

We came into a warehouse where the barrels are designed. Brandy explained how they are constructed out of staves from different woods. Maker’s Mark uses American and French oak, as well as a French variant with hints of mocha. Each imparts the bourbon with a distinct flavor profile, given that all the barrels are newly charred before they are filled. It shows just how finicky these woods can be when compared to each other, and how difficult it can be to get the flavor right.

Surely a highlight for many on the tour was seeing the line where the bottles are dipped into the famous red wax. It was just an assembly line with seats on each side, with vats nearby where the wax is kept warm. We also saw a portrait of Margie Samuels that is displayed in the wax room. She serves as an inspiration to everyone there as the true impetus of Maker’s Mark’s craft image.

Unfortunately, the dippers were not on the line during the tour. It turned out that they had actually ran out of bottles. As they couldn’t do very much about it, I believe they had been given the day off.

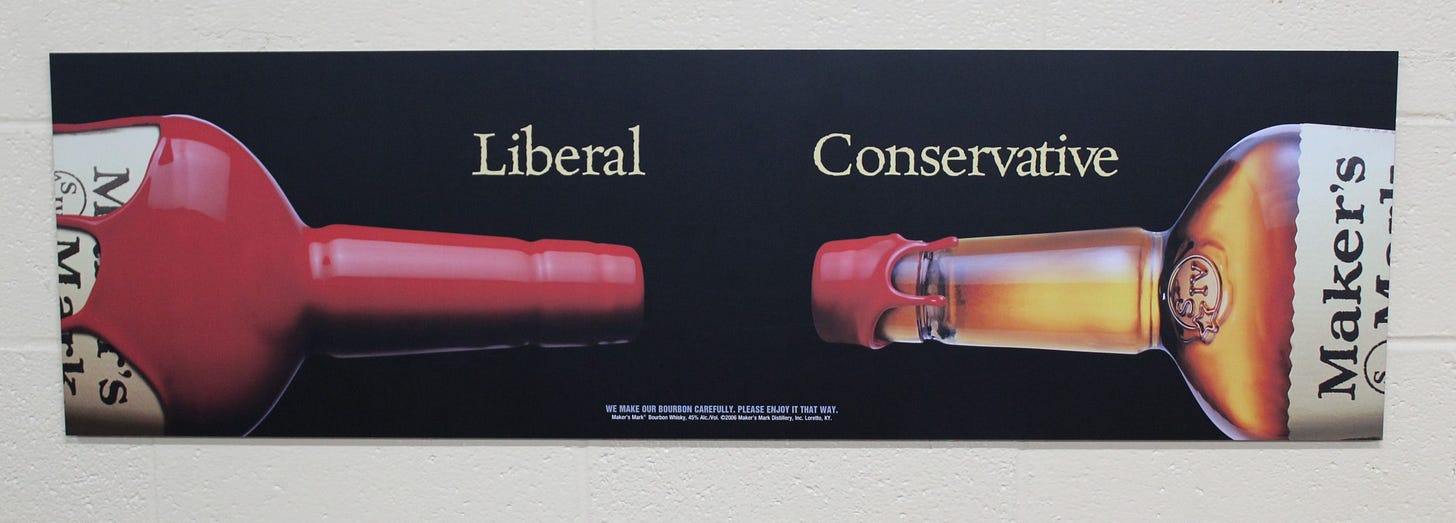

I found the posters inside hilarious and clever, and this one tries to diffuse the tension in a playful way. The “liberal” extreme, called a “Slam Dunk” or an “Oops” bottle, is an occasional occurrence.

We sampled five different products once we got to the tasting room. The first was your regular Maker’s Mark, while the second was Maker’s 46 divined by Bill Samuels Jr. with French oak staves. The third was Cask Select, a “burnier,” but still smooth, gulp. We also sampled Cask Select 46, as well as another which I didn’t identify fully. However, it was the Taste Panel which stood out to me the most, because it was aged in barrels with four different oak staves built into it. It had a uniquely complex flavor, and it was one of two which were specially sold there at the distillery.

Before we entered the gift shop, we walked through a special barrel room. The ceiling was made of a surrealist canopy designed by world-renowned glass artist Dale Chihuly. Titled The Spirit of the Maker, it was unveiled in 2014 to celebrate Maker’s Mark’s 60th anniversary. Made of 750 different hand-blown shapes, the piece is also Chihuly’s first public artwork installed in Kentucky.

I instinctively knew I was going to take a bottle of Maker’s Mark home with me. I also made it a point that I was going to hand-dip mine, an experience that sets the distillery apart. The issue was, for a couple of minutes, which one I was going to get. I ultimately chose the Taste Panel batch because it was my favorite sampling, and because it was truly unique only to the distillery. It was rather steep for a cheapskate like me at $80, but the total experience made it well worth my money.

It was pretty cool to dip my whiskey into the wax. My cover is not nearly as uniform or not, though.

After Dad suggested it, I asked Brandy to sign my bottle. She did so in red marker, so it’s hard to see against the amber aqua vitae. I suspect that I was the first to make such a request, but she was happy to do it for me. It’s one of those odd-ball touches that makes my batch all the more unique.

Knowing we were more or less behind, we purposefully, but calmly, made our way back to the visitor’s center where Mom and I had our mixology class. We got back and were shown to the table on which four pairs of shakers, Hawthorne strainers, stirring glasses, bitters and Old Fashioned glasses were set. Some Luxardo cherries and what looked like jam were in the middle. There was also a bar set up with only Maker’s Mark (some product placement there, obviously).

Dad, thrilled as he was, went to either sit in the waiting room or go back to the car to take a nap. Though he was our designated driver, he missed out on the fun we had with a hoot named Austin.

Let’s talk a little here about Austin, the bourbon specialist who led our mixology class. She was irreverent, energetic and downright fun. You could tell she had served her fair share of drinks; she was able to encapsulate the two types of people you would see at the bar – or at your own house.

There are your friends who you can let have a little bit more than a jigger of your liquor drop into the glass, provided that they behave themselves. Then there are those who are hell-bent on taking down as much alcohol as possible.

The class was made up of Mom and I, a couple from Atlanta, one from Detroit and another from Columbus. As I expected, we all, including me, eventually opened up as the drinks came and went.

We learned some necessary skills about handling your “tools” at the bar. It did not occur to me until the class, but it is always advisable that you hold your jigger over the glass (simply because liquor is expensive). I also learned how to properly hold a shaker while shaking, as well as how to stir. This last one is not as easy as it looks, folks, because it’s just all in the wrist. I think Austin said it took her at least a month to really get it down pat just practicing with a jug of water and ice.

Perhaps the most important concept is that you need SSS – sweet, sour and spirit – to make a good cocktail. Indeed, Austin provided that this makes up 97 percent of cocktails you’d want to drink.

We made a Whiskey Sour (as well as the “Boston” variant with an egg white), a whiskey highball, an Old Fashioned version with chocolate bitters and a Boulevardier, my favorite out of the group. All of them contained some sugar in one way or another, and my blood sugar paid the price for it.

Throughout the class, Austin had no qualms spilling booze and bitters onto the carpet. She told us the room was “finally” going to be renovated in the next few days, so she really did not care. We all ended up taking a selfie together, and we had a wonderful time with it. However, Mom and I finally had to face the harsh and spinning reality of being a little more than just under the influence.

I shouldn’t at all overlook the fact that we both had FIVE complete drinks when it was over. This was the first time that I described myself as being truly intoxicated. My vision seemed to whirl, though I was able to focus on an object. All I can really add more here is that I’m glad we had Dad as our designated driver.

We made our way back to Bardstown to get some grub, as we had had nothing to eat since breakfast (a bad judgement with respect to how Mom and I felt after our cocktail excursion). It was a little before 6 p.m. when we got back into town and parked in front of the Talbott Tavern. We (especially I) made it a point in our planning to eat at this historic landmark for dinner. The last time I remember seeing it, Mom went inside an antique shop beside it that, apparently, is no longer there.

We thought the tavern was surprisingly busy, even for a Saturday evening. However, it occurred to me that the Talbott is still an active inn after 240 years. Indeed, it is considered the oldest continuously-operated historic travel stop in the country. During the late part of the 1700s, it was the westernmost stop on a stagecoach route from Pennsylvania. The tavern also claims to have the oldest bourbon bar that you can find in Kentucky or, for that matter, anywhere in the United States.

The Talbott Tavern has quite the history in and of itself. It has hosted important figures such as a young Abraham Lincoln (while his family was locked in a land dispute that ultimately forced them to move to Indiana), John James Audubon and John Fitch, the inventor of the steamboat. George Rodgers Clark used it as a base to gather materiel and supplies for the Illinois Campaign, during which he seized the crucial British posts in modern-day Kaskaskia, Ill. and Vincennes during the Revolutionary War. For the fans of the symphony, Anthony Philip Henrich, who went on to found the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, played his very first composition at the tavern in 1817.

The Talbott Tavern has hosted European royalty on a couple of occasions. Queen Marie of Romania is one of them, and so is Louis Philippe I, who stayed at the inn in 1797 while in exile after being found in support of restoring the monarchy after the French Revolution (he was the Duke of Chartres at this time). It is believed that either his brothers or someone in his entourage painted the once-colorful murals which were uncovered in one of the second-floor rooms in 1927.

The most infamous guest in the tavern’s history certainly has to be the bad-boy outlaw Jesse James. According to legend (though I really have no reason to doubt this as being true), he stopped by the Talbott and had a little too much to drink at the bar. He was told either to leave or to go sleep off his inebriation. He ended up struggling to the room which contains the murals, only to then shoot at the walls after seeing “butterflies” flying in them. The dozen or so bullet holes can still be seen.

The Talbott Tavern is known for its paranormal activity. The apparitions of a “lady in white” and, supposedly, Jesse James have been seen, and doors opening and closing by themselves, as well as disembodied footsteps late at night, are a daily occurrence. A piano is also known to play by itself.

Unfortunately, an electrical fire which broke out in 1998 severely (or perhaps irreparably) damaged the murals, and mostly destroyed the second floor in general along with the roof. This is why the suites have a much more modern appearance as opposed to the entrance and dining areas.

I had the Talbott’s fried chicken, while Dad had their Hot Brown which had a good amount of flavor to it. I can’t remember what Mom had for her dinner, but she felt much better afterward. I appreciated how friendly our server was, as she basically knew we were from out of town. After I asked about the murals, she actually gave me a packet highlighting the tavern’s historical points.

We then headed back to our hotel room in Louisville and slowly capped our day. When my sister finally got back, we all went to bed around midnight.

Day 3: The Short Goodbye

January 4, 2020

We were on the road back to Greencastle by 10 a.m. on Sunday. Before that, though, we met up with my sister’s boyfriend one more time at a Wild Eggs. Needless to say, it was very good. Even the small chains can pump out some quality grub in Derby City. It was a good, but short, goodbye.

Thus ended my sampling on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail. It won’t be very long before I go back.

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[author title="" image="https://www.bannergraphic.com/photos/34/41/96/3441969-S.jpg"]Brand Selvia is a staff writer for the Banner Graphic newspaper which serves Putnam County, Indiana. He is passionate about history, connections and classic cars. “Brando” loves to chat over a cup of coffee, and also enjoys joyriding and going to car shows in his 1974 Volkswagen Beetle.[/author]