A Shared Human Experience

DePauw Music Professor Eric Edberg shares his love of the cello with anyone who will listen. And many of us do. Not just because he's good, but because his music draws something out of us which we've kept locked away.

by Donovan Wheeler photos by Jiawei Fang

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]en minutes into our conversation, I put down my pen and voice recorder while DePauw music professor Eric Edberg picked up his cello. As we had spoken during that first interval, sitting by the front entrance to Greencastle’s Starbucks, only a few people had gathered to take in why a man sporting an enormous classical instrument was chatting up about his life and music. And by "few people," I really mean “no people.” Then an amazing thing happened. As Edberg ran his bow across the cello’s strings, a high school student, Ashton—a junior—took a seat across from him and watched. Entrapped by the sounds of the Prelude and Allemande to Bach’s Suite #1 (in G-Major), the teenager’s eyes darted from Edberg’s dexterous finger placements along the neck of the cello, to the movement of the bow above the bridge, and finally to the serene expression of the man holding the sound. His head down. His eyes closed. It’s cliché to say that Edberg and the cello had become one complete instrument, but no other expression aptly captures what happened. When the final note lingered into the vapors of latté and cappuccino mist swirling around us, the high-schooler approached the cellist. “That was really good,” she said. “I was standing in line, and I said to my mom, ‘I hope he plays before we leave.’” “You see what happens?” Edberg said to me beaming. Donovan Wheeler: Why the cello? Why aren’t you wearing tie-dyed t-shirts and playing in a rock-and-roll band at a bar until 3:00 in the morning? Eric Edberg: “I started the cello when I was 11, and my mom was a pianist who taught the piano at home in the basement. She had played a concert with a Jewish community center, and her piano teacher was the conductor of the orchestra. Additionally, she and my dad had built a harpsichord from a kit, and had played Vivaldi’s ‘Four Seasons’ with it. At one of those performances, I recognized the lady playing double-bass was the person who taught strings at my school, and I mentioned that to my mom. So Mom introduced me to her backstage after the show, and she looked at me and said, ‘We could use a tall boy to play the cello at your school. Would you like to try that?’” “My mom said, ‘He’d love to...’ I was hoping to play the double-bass, but I thought, ‘I’ll do this cello thing, and if I don’t like it, I’ll move over to what I really want to play.” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

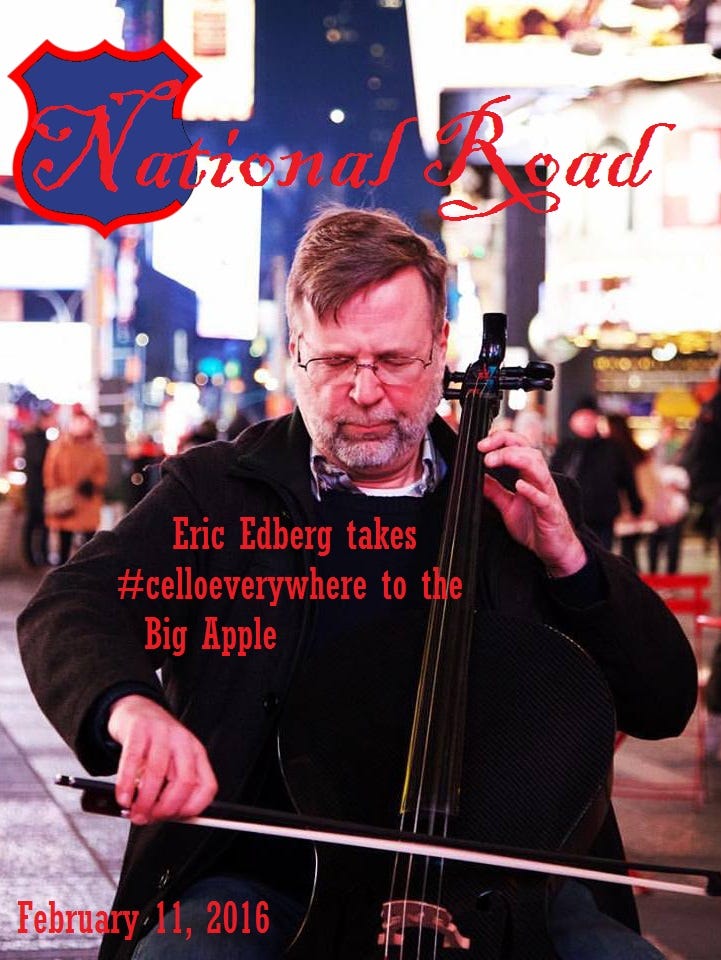

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] DW: So this filled a vacuum of sorts? EE: “Well, for starters I was no good at all at sports, and I quickly lost any interest in that. Then at home…my parents were kind of snobby about music. They didn’t like jazz…they didn’t like rock and roll…they didn’t even own any vinyl recordings of pop standards…no Sinatra, no Dean Martin…that sort of thing. And I was also a sort of ‘loner’ as a kid. I didn’t hang out and listen to rock music like other kids my age. I did listen to a lot of cello recordings, however, and then I got into the Boston Pops. Eventually, by the time I was 16 I was buying Beethoven’s Symphonies and things like that.” DW: Talk to me about your trip to New York and your #celloeverywhere experience. How did that come about? EE: “I had read about Dale Henderson who was going to the New York subways and playing Bach right there on the platforms. So in 2010-2011 I was on sabbatical, and I spent the second semester in New York. One day I got off the subway at my stop, and there he was. I was so thrilled to meet him because one of the reasons I was in New York to begin with was that I was trying to think of new ways to bring classical music to new audiences. He put a stack of his promotional cards on a music stand and said, ‘No tips, please. Just enjoy the music.’ And I thought, ‘I’ve got to get in on this.’ So I went to the subway and played as well, and I was surprised by how many people approached me and said such kind things to me. One woman—I think she’d probably had a few cocktails for that matter—gave me a big kiss and told me she loved my music.” DW: Did the two of you collaborate on anything? EE: “In March of that year, Dale, myself, and some others organized a series of string players to scatter throughout the city and play Bach on his birthday, which was on the 21st. It continued, and now it’s happening worldwide, in something like 50 countries. Dale swears it was all my idea, but I don’t know about that.” DW: So did something about that trip to New York inspire you to turn it into a photographic experience? EE: “I had gotten the idea to pose for a series of photos of me playing the cello in unconventional places about two or so years ago. At first I conceived it as a ‘photo experience,’ largely because at time I had fallen in love with a guy who was also a photographer. We went to the Smokey Mountains and decided to shoot some photos while there, and we came out of that trip with some really cool shots. So, when we decided to go to New York, we knew we had to repeat what we had done in Tennessee.” DW: And…? EE: “The first couple of days there, we were able to get some great shots of me around and in Rockefeller Center, but the temperature hovered in the mid-to-low 30’s, so I actually couldn’t play…or I suppose I could, but you wouldn’t have wanted to hear what I was making in those conditions. That was disappointing, because as much as I enjoyed the photography, I really wanted to play for people and interact with listeners.” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] DW: Then you go to Central Park… EE: “It was warmer…upper 30s and very sunny. As we entered the park, we spotted a handful of counter-terrorism officers. As I walked past them, I was hit with this impulse to play for them. I walked toward one of them…to ask if they would like to hear some music…and the nearest officer turned to me quickly.” “‘STAND BACK!’ he said. And I thought, ‘Okay…don’t shoot me!’ I get why he did that. They operate with a sort of zone of contact which is part of their protocol. Eventually, I found a little niche by the entrance to Columbus Circle and played for about 15-20 minutes. Passers-by would stop, and watch, and shoot some pictures. Several people took my calling cards which were set up. It was exactly what I was hoping would happen.” “As we gathered our gear to move to a new location, one of the officers approached me and asked if they could have a copy of the photos. I was touched. I assumed they hadn’t been listening because they never turned their eyes to me. But later that week, he found me on Instagram and thanked me. He also sent me an email and thanked me. His mom even sent an email sharing how much it affected her son and his colleagues.” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] [dropcap]W[/dropcap]e take a break, and Edberg returns to his cello. Picking up from the Allemande, he continues with the same Bach piece—this time gliding through what he calls the Courante. It’s less familiar than the Prelude, which I knew sounded familiar before he told me that advertisers had used it hundreds of times in television commercials. Again, as he plays, Starbucks appears desolate. An older fellow with a short, cropped haircut is obviously tutoring what looks like a DePauw student. Something tells me their working on some type of math. Edberg’s rhythm hypnotizes me…and I’m thinking in pleasant tones about math…and how much I hate it. The bizarre melding of contradictory emotions which only music can accomplish. When he puts down the bow, a young woman appears from a hidden corner of the shop. She used to play the cello, and she thanks him—deeply—for connecting her to a past she still holds onto. DW: So do you play the cello the way guitarists and bassists play? By stringing sequences, chords, and basslines together? Or do you have to work through it on a note-by-note basis? EE: “For many of us who play the cello, we work through it linearly…as a melody. So we work through a piece more on a note-for-note fashion, but much of the memorization is kinesthetic. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten more into the process of memorizing chords. And this is what’s particularly interesting about Bach: He’s able to construct everything harmonically, which brings out those harmonies and implies the basslines all the while maintaining a continuous melody. He does this in so much of his work. He does this in three partidas—which have similar movements to the suites—and also in three, four-movement sonatas for solo violin…which are always amazing when you listen to them.” DW: Is this Bach piece fluid and set up for easy movement? Or does it have some technically nasty spots in it? EE: “It has some technically difficult spots, but I first learned to play it when I was 12, and much of it is ingrained in my muscle memory now. And it’s just such a friendly piece. It has that nice poignant quality to it.” DW: It’s familiar…at least the beginning. EE: “YoY o Ma’s version is particularly famous. I remember I once played a wedding, and the bride approached me and said, ‘Can you play Yo Yo Ma’s Prelude from Bach in G-Major…’ If you’re not really aware of classical music you probably would say that as if you were requesting ‘Taylor Swift’s Bach’ or ‘Adele’s Mozart’ It reminds me a funny book I read for violinists titled: Who Wrote Vivaldi in A-Minor?” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] DW: Does Yo Yo actually make Bach his in any way? EE: “Yo Yo does do a distinct version of it, but the interesting fact is that—because I do free-improvisation and got interested in the intellectual underpinnings which have allowed for that—what you learn is that ‘The Prelude’ was originally just a warm-up which led itself to a lot of improvisation when it was first composed.” DW: Really? EE: “It wasn’t until the 19th century that the idea of musical compositions as ‘great works of art’ occurred to people. You can say it was a construct, or you can say it was a recognition—whatever you want to call it—but up until Beethoven, there really wasn’t a composer who thought of himself: ‘I am a great artist.’ Of course the entire concept of ‘great art’ developed in German Romanticism at about that time. Once that happened, these compositions took a more concrete and permanent form, and the idea that—as a musician—you were a sort of ‘co-creator’ with the composer died away.” DW: So each player does make it his or her own then? EE: “If you listen to 30 recordings of this performed by different people, they sound like different pieces. And I think that this co-creative element is simply intrinsic to music-making because no matter how many sheets of paper you put it on, it always comes through the medium of human beings. Consequently, it manifests itself in different ways.” [dropcap]E[/dropcap]dberg resumes his take on Bach and again garners well-earned congratulations from people we had no idea were listening. When he stops, I turn to the cello itself and ask him to walk me through it. It’s a fascinating instrument. Like its more popular cousin, the violin, the bow vibrates the strings, the vibration channels through the wooden bridge into the shell. And there, inside the hollow body of the cello, sits the sound post: a wooden dowel rod carefully wedged between the front and back walls of the instrument. EE: “Where the sound post is located—and getting it put in just right spot—makes a huge difference in the quality. People who can really hear the difference and know how to position it are very much sought after. Rene Morel in New York was so good at it, the legend went that he cost $50 a tap. People came from all over the world to have him position their sound posts.” DW: Making money in classical music is becoming a challenge today. What are classical organizations doing to preserve the art form? EE: “If you’re a large organization like the Indianapolis symphony, then you’re trying to bring in a young audience…because they’re going to be your old audience in 30 years. So it’s very important for classical music operations to connect with people in their 20’s and 30’s, even if they’re not in a position to be million-dollar donors right now. There’s also movement toward chamber orchestras and small ensembles, and there’s a big explosion of groups which are self-governed. These are organizations where the musicians also handle much of the day-to-day administrative elements of the operation. They work under a consortium model rather than a hierarchical model, and as long as it doesn’t get too big, that’s becoming the thing to do.” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] DW: So the focus is on localizing, then? EE: “I think that if you’re a musician today you need to be thinking about how can I make a difference with my education. If you broaden your expectations you’re going to find yourself with more opportunities rather than, say, hoping for that one paid oboe position in an orchestra which may find itself changing from a 52-week orchestra to a 30-week orchestra…or one that shuts down altogether. But on a more basic level, it’s important to be able to play in a setting such as this one right here, where you can win over people and inspire them with the music.” [dropcap]T[/dropcap]his intimacy Edberg speaks of does not ring hollow. His mother, the pianist who taught him to love music and encouraged him to pursue the cello now fights Alzheimer’s disease, a journey Edberg has affectionately detailed via frequent Facebook posts. EE: “When I was teen I often believed I was ‘preparing for Yo Yo’s job.’ Then I had an aunt who was in hospice care. I would borrow a cello from a music dealer and play for her. All my concerns, all my worries just dropped away. The music became a conduit for the love we all felt for her. It was passing through me, and I was just a medium like the cello itself. That moment changed the way I thought about music, and classical music specifically…the healing power of it on so many levels. After that I started playing in hospitals and nursing homes quite often, and I discovered that all of this allowed me to escape the ‘perfectionism’ which had plagued me when I was growing up.” DW: And now with your mother? EE: “After my mother lost her ability to speak effectively with me, she would still sit at the piano, and we would play together. She could stay with me musically. The day finally came when she couldn’t do that anymore, and she put away the piano keys, but it was so profound how she could still communicate through music even though she had mostly lost her ability to do so with language.” [dropcap]A[/dropcap]s we ended our conversation, Edberg quoted New Zealand’s Christopher Small—the late musical author famous for shifting the focus of music from its status as thing (noun) to its actual existence in our lives as an activity (verb). Of music, Small called it the “shared human experience.” No doubt, were Small alive and here at this little Starbucks, he may have been able to point to Edberg’s performance by that entryway door and say, “See? This is music.” When I shook Edberg’s hand and walked away from the coffee shop, I still heard the tones of his cello still echoing through the walls behind me. Eric Edberg wasn’t finished with Bach, and no doubt he also wasn’t finished offering a moment’s serenity to the hectic minds congregating over caramel mochas and skinny vanillas as well.

[author title="About Donovan Wheeler" image="https://scontent-ord1-1.xx.fbcdn.net/hphotos-xla1/v/t1.0-9/12227583_10205212537208138_868143467060930572_n.jpg?oh=ae18974f3b92d1be741f9109e6ad1d17&oe=576F2C2F"]Wheeler proudly teaches AP Literature and AP Language to some bright and lovably obnoxious kids in a small college town. He is the senior editor for the craft beer website Indiana on Tap and writes for ISU’s STATE Magazine. Since putting in a pool he can now dive in head first (with goggles), and he has mostly stopped throwing golf clubs, but he still hates to fly. [/author]