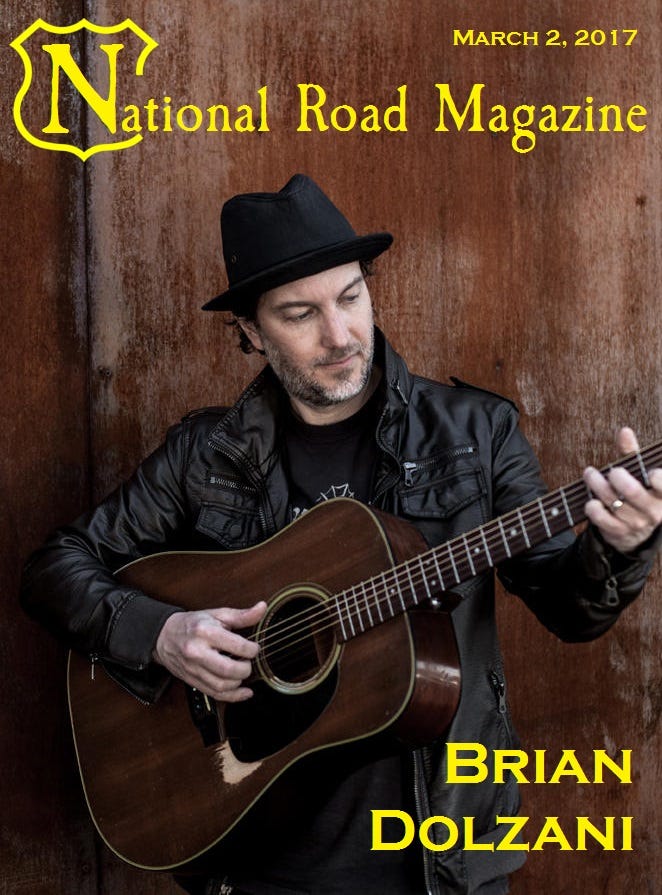

Brian Dolzani: At the Edge of the Shore

Brian Dolzani's life on the road embodies the transitioning of a young man tortured by the early death of his father into an experienced musician finding peace and thriving as an artist.

by Donovan Wheeler photos by Josh Wool and Brian Dolzani

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n Lord of the Flies William Golding’s protagonist, Ralph, observes that we spend much of our lives watching our feet—an ironic statement given that he’s trapped on an island, yet largely free to go anywhere he wants to on that island. Of course, when we imagine ourselves stranded on an uncharted lump of rock, surrendering our free will is easy. But when we go about normal life in familiar haunts, we inherently embrace the idea that we are the masters of our own future. The truth, however, is that we’re all stranded on islands—a handful are of our own making. Most of them are not. On those isolated plots we cut through our jungles. We run into a plethora of symbolic intersections, and we scribble out the routes for our lives, but these are small choices. The big choices are not ours to make. We don’t choose when or where we’re born. We don’t choose our gender, our race, our biology. We don’t choose where we grow up, and we don’t choose the tragedies which befall us along the way.

Such was the case for singer-songwriter Brian Dolzani. When he was 15, Dolzani’s father died in an automobile accident. In an instant, with no time for any sort of goodbyes, he found himself emotionally shipwrecked, forced to navigate the rest of his childhood and emerging adulthood without the paternal guidance most of us take for granted.

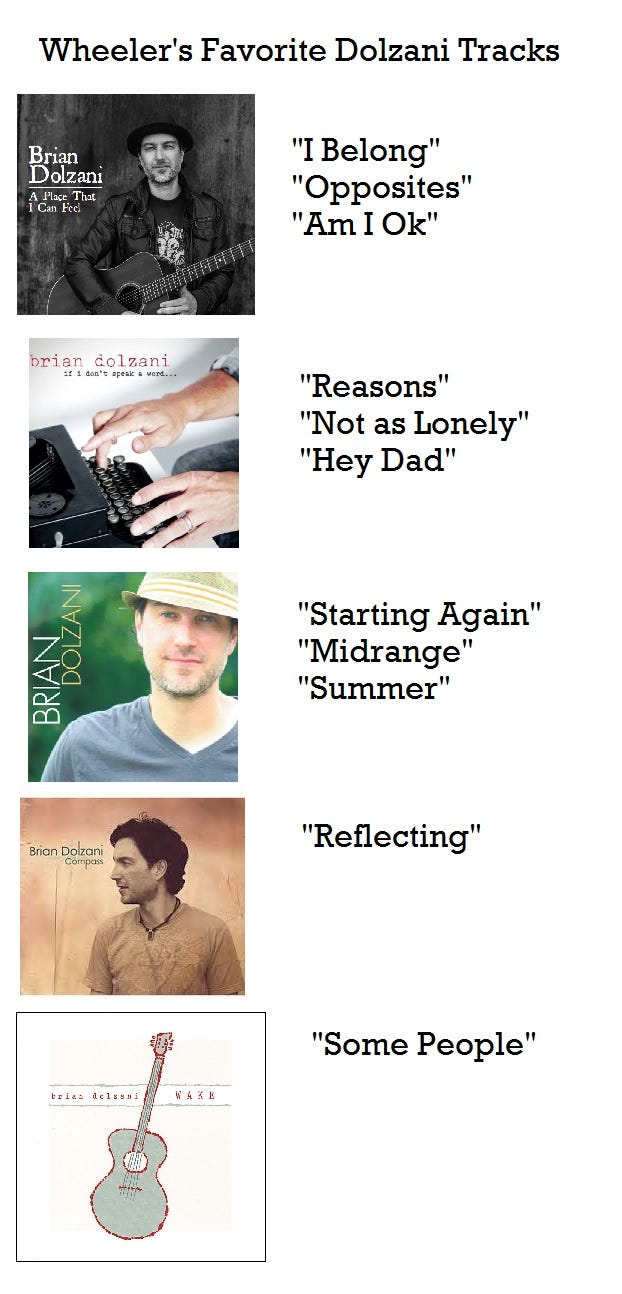

“I feel like I spent [the next 10 years of my life] avoiding [the loss of my father] or running from the pain,” Dolzani says. “Then [as I approached my late 20’s] I went straight for it, both by writing my feelings and also [by pursuing] a lot of self (and professional) therapy…becoming as self-aware as I could be.” Dolzani’s father wasn’t a musician himself, but he loved the art and shared it with his son in the form of a prized vinyl collection, a gathering of tunes which would shape the eventual songwriter’s prolific career. He would crank out more than a half-dozen full-length albums, each of them showcasing the progressive development of his soft vocals—a sound often compared to Neil Young or America’s Gerry Beckley. His anthology is a narrative collection of personal songs loaded with milestones marking his progression from that young troubadour facing the painful loss which molded him to the seasoned traveling songwriter making peace with everything beyond his control.

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

Donovan Wheeler: Besides its effect on your immediate life, how has the loss of your father impacted you on a deeper level in terms of life philosophy?

Brian Dolzani: “I’ve probably had this aspect from birth, but it heightened my insecurity about life and who we are—knowing that obviously we don’t live forever, that death can come at any time, and that there probably is something more than what’s here on earth. It reminds me that we should know ourselves as fully as we can before it’s too late. It heightened my thoughts about an afterlife and made me cling to one, perhaps as the only way to justify or explain his death…or at least look for a reason why it happened.

DW: Some of your tracks are overtly personal, while others sound very universal. Do you sometimes switch from that intensely first-person voice to something more general and omniscient, or is every song a first-person experience which some of us interpret differently?

BD: “That’s a good question and observation. I think my deepest wish is for all my songs to be deeply, overtly personal. When I veer from that, it’s because I’m avoiding self-consciousness, or because I feel like I’ve said too much. I doubt that my personal story would be of care to anyone. Although I’ve found that it’s my most overtly personal songs that make the most impact. One part of me thinks that trying to be ‘universal’ and omniscient is trying to sum up life as I wish I were able to. But sometimes that doesn’t really connect. It’s more the real here-and-now details that often connect the quickest.”

DW: You have deep New England roots, but you’ve spent a lot of time in the South. Your Nashville blog-videos from a few years ago were fascinating, by the way. In what way has your Northern upbringing blended and/or contrasted with your Southern exposure?

BD: “Oh thanks. I’m glad you liked them. I really love both regions. I’ve discovered more recently that the South has the deep folk and timeless Appalachian music roots which really resonates with me, and the warmer climate and slower pace seems to match my inner style. I also just plainly think that people in the South are more involved with live music, and my style of Americana.”

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

DW: You’ve been compared vocally to Neil Young and America’s Gerry Beckley. Given that none of us are immune to comparisons and influences: To what extent do those comparisons work for you (in terms of relating your music to new listeners) versus work against you (in terms of overshadowing your own uniqueness and accomplishments)?

BD: “Yes, that’s a funny thing. I’ve heard and liked ‘Horse with No Name’ ever since I was in high school, and I used to play it at gigs. Recently I’ve said to myself ‘Man that guy sounds just like Neil!’ [Laughs]. It’s a matter of just facing what’s real. There was a time in the early 2000’s where sounding like Neil wasn’t doing me any favors, at least here in New England and in Connecticut. I’ve tried to veer from that, but I’m glad I’ve come back to my natural sound and style, and instead found my audience based on it. And I have to realize that I make comparisons, too. It’s ok to give people a ballpark when talking about your sound. It can also be hard though because there are people who like me but don’t like Neil’s singing at all. My fear is that someone who doesn’t like Neil for instance then dismisses me because of the comparison. That’s unfortunate, but I suppose things in life like this happen.”

DW: Besides the early vinyl influences from your father’s record collection, what additional influences shaped you musically?

BD: “The music that hit the hardest hit me in high school: the second-coming of classic rock. Zeppelin, the Dead, everything on rock radio. I started as an electric guitar player, never intending to sing. But eventually the wood of the acoustic guitar won my heart, and the sound of the strings vibrating off the wood still does today. The natural resonance of the acoustic was what hooked me, like it belonged to or came from nature. That’s what influences me most—trying to recreate what I think is nature’s sound. That’s when I realized I had things to say. So I had to write songs.”

DW: What new styles and artists are inspiring you today?

BD: “I don’t think anything that’s truly ‘new’ is inspiring me, as much as it is there are many artists returning to an older form. I just love all the great Americana and country songwriters out there now, seeking and expressing their authentic voices, and the voice of the human person. That’s what I’m trying to do. Write something real. No crazy gadgets required.”

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

"My oldest work comes across as very naïve and escapist. But that’s who I was back then. I would do anything to not really be here, including singing more about fantasy and what I wished would be true instead of what was. More recently I’ve gotten a lot better at writing details and observations that are more ‘here’ rather than ‘somewhere out in the universe far, far away.’" Brian Dolzani

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

DW: Your transformation musically and lyrically is evident when I listen to your collection chronologically. It becomes quite pronounced when I bounce back and forth between 1998’s Fall Into Me and 2015’s A Place That I Can Feel. You have recorded albums using several different styles from simple acoustic to the “live” setting, to mixed tracks. What do you like and dislike about these approaches?

BD: “Yes, I agree the difference is very pronounced! [When I look back on it] I admire my spirit and willingness to express and put myself out there long ago, more than the actual results. I was undeveloped for a long time, yet I always pursued my artistry (more accurately my attempts at it).”

BD: “Sometimes the different ways of recording are governed by resources: money, time etc. Fall Into Me was recorded at home by myself because I couldn’t really imagine going to a real studio with a band and producer and paying a lot of money (money I didn’t have anyway). I did mix it in a real studio, but from the start my music felt like it should just be me. I didn’t feel like I wanted or needed to involve anyone else. I remember the producer who mixed the record wanted to add a shaker to one song. And I was shocked! On one hand I thought ‘how dare he make a suggestion, isn’t it good as it is?’ But on the other hand I worried ‘well if he plays on the record, it’s not completely mine anymore.’ I can relate it to losing my dad as a boy. Because he was inexplicably taken away from me, I protected the next thing that was so important to me, my music. I didn’t want it to suffer that same fate.”

BD: “Then my next record, Living, was fully produced in Nashville in 2001 by a producer who ran an indie production company. He was a real nice guy, and it was an overall a pleasant experience. Yet it was also an expensive churn-and-burn recording style. He hired studio guys who were amazing, but I didn’t know them and never talked to them again. As a result I felt like I was almost not part of the record. That may be unfair to say because in the moment I thought I was getting the best record ever, and it was pretty cool. But later on I asked myself ‘was I even there?’ Even though I did put a lot of heart into those songs and they meant the world to me I struggled with that album and pretty quickly abandoned it after I released it.”

BD: “But by the time I got to If I Don’t Speak A Word (with Nashville producer Neilson Hubbard, my good friend whom I trusted with my deepest feelings), and then A Place That I Can Feel, I was much more comfortable working with other musicians and still feeling like it’s my music.”

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

DW: How do you feel about the results of your work in Tennessee making the tracks for A Place That I Can Feel?

BD: “It was the most fun I had making a record so far. All the band songs we tracked and sang live, and I love tracking that way. There are limitations to recording to tape, of course, but the sound you get is the most natural in my opinion. And Fry Pharmacy, the studio, has such a unique room sound. It just begs to be captured on tape.”

DW: When you were a beginning singer/songwriter creating your first rounds of work, what did you anticipate when you peeked into the future?

BD: “My only thought was that I would be doing this forever. It was never a temporary or trial thing (‘if my second album tanks, I’m done’). Of course I avoided putting myself in direct competition with charts or sales numbers or anything to see if I win or lose, if I should continue or quit. One, because I worried I’d obviously fail compared to others, since my goal was to be an individual, and in terms of the world, I felt like individuals/outsiders always ‘lost’; and Two, because I knew I was in this for life. So charts and numbers didn’t ever matter.”

DW: Now that you’re a half-dozen records into your career and life, what do you think about that younger version of yourself when you look back?

BD: “When I look back I see a dreamer who found it hard to relate to people and painful situations. I think of my earliest songs as often reaching for a different universe, one where pain and discomfort doesn’t exist. Having said that, I wrote a lot…a lot…of really painful songs that I never released because I thought the world didn’t want to hear them. It seems like the ones I released were ones where I was trying to create a separate, less painful world (while suffering behind the scenes). Consequently my oldest work comes across as very naïve and escapist. But that’s who I was back then. I felt I was a highly spiritual person in a painful bodily existence. So I would do anything to not really be here, including singing more about fantasy and what I wished would be true instead of what was. I’m still working on that. Again that’s just my personality. Grounded is not something I naturally am. Having said that, I also think that more recently I’ve gotten a lot better at writing details and observations that are more ‘here’ rather than ‘somewhere out in the universe far, far away.’

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

DW: Your 2016 track “When God Asks You Why” blends all those personal elements with references to world events. Do you see this as a sort of artistic turning point, or have you always been doing this in one manner or another?

BD: “I do think it was a new direction, for sure. I don’t tend to write about current events…almost never. But things last year were really unable to avoid. As for the personal aspect, I didn’t want to just ‘sing the news.’ I figure anyone can do that. Where’s the uniqueness in that? However, through this song, I’ve realized that yes, sometimes it’s good to just write what’s happening and comment on it. It’s a pretty simple idea. I still worry that that asking the listener to think about what God might say to them, and them to God, is a bit of stretch (if they even believe in God). It’s certainly existential and not everyone wants to go there. But I’m proud of the song and a lot of people do react to it. At first I wasn’t sure if it was really ‘me’ or not, but it is me.”

DW: Tell me a little bit about the feelings you express in your bio regarding the impact of the digital world on the human experience. How does music combat the elements of that which trouble you the most?

BD: “For both the player and the audience I really think it comes down to live music. It’s a paradox with me, because while my imagination is highly expansive and can go anywhere at any time, I don’t like to just live in the mind. And to me that’s what a lot of technology is, just following an idea to no end. My immediate question is always: Just because you can, should you? The point I’m making is that very quickly I get bored with ideas and want to hold something, see someone, feel something (and someone!). Cold and digital doesn’t thrill me for long.”

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]rian Dolzai still navigates his way around the island of his life. His shores haven’t touched big recording contracts nor have they offered him trips to the stage at the Grammy Awards, but they do document a life spent making peace out of anger, order out of chaos, and hope out of despair. “What I seemed to have learned after all these years is that it really is about the journey. Even more than I realized.” Whether he speaks of the myriad ways he’s recorded albums, the long days on the road, the nights playing both “great gigs and worthless gigs,” or the hours spent chasing one topic after another as a songwriter, all of it has been about the moments on his own shore, not some unseen goal over the horizon. “It’s the journey,” he repeats. “That’s what I love the most. Going far and the getting there, and then going farther.”

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] [author title="About Donovan Wheeler" image="https://scontent-ord1-1.xx.fbcdn.net/v/t1.0-9/13413045_10206476443925016_3719335501835627694_n.jpg?oh=b3c2dd713a7e1d8c1dbbdc8f07189b18&oe=5902C626"]Wheeler proudly teaches AP Literature and AP Language to some bright and lovably obnoxious kids in a small college town. He is the senior editor for the craft beer website Indiana on Tap, and he also writes for ISU’s STATE Magazine, NUVO News, and VisitIndiana. Since putting in a pool he can now dive in head first (with goggles), and he has mostly stopped throwing golf clubs, but he still hates to fly.[/author]