Cari Ray is Not Pretending

by Donovan Wheeler photos by Tyler Zoller

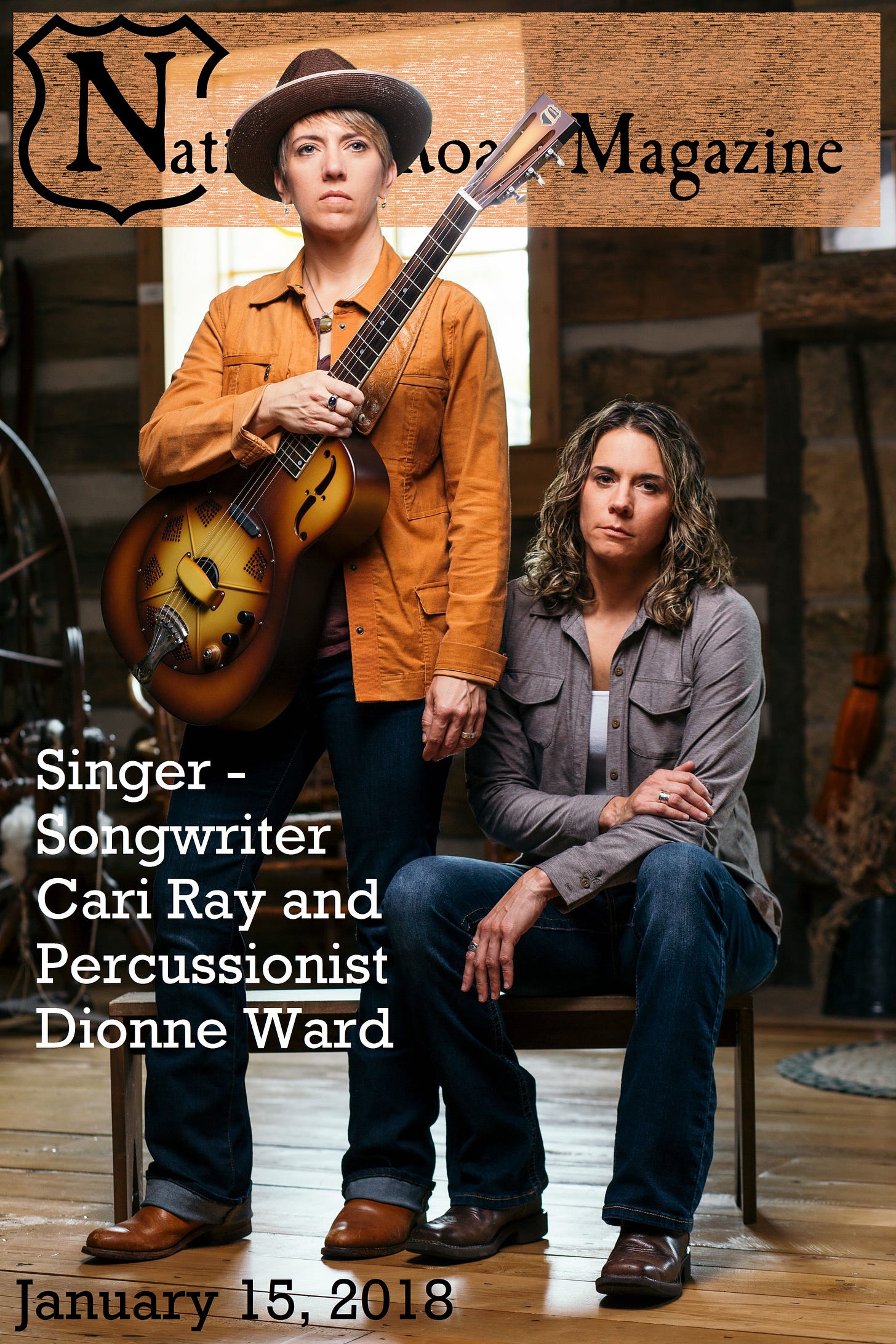

Compensation is often hardwired into the DNA of the music business. Strong singers figure out how to play a few chords to get by. Great fret-masters eke out a tepid set of vocals for the same reason. Then we sit down and watch someone who can nail them both. Cari Ray’s controlled work across the strings of her National Triolian (a throwback guitar paying homage to the models made popular by Depression Era performers) is in itself impressive, but when she layers that melody over her finger work—and when she adds the backing harmonies of her equally talented partner, Dionne Ward—she has created a musical duo that is justifiably grabbing the regional music scene’s full attention. But if you look deep into the crystal ball and scan the either of the past, a different Cari Ray is cutting her professional teeth. In that window, framed by wisps of a swirling fog, you will see a younger Ray gigging in a Circle City bar, offering up a new tune, created sometime in the dawn of her career. The song—something contemporary… consumable… mainstream—isn’t the only thing that’s different about her. She’s hatless, for one thing. Swaddled in urban attire, casting herself as a fresh, hip artist evoking her fresh, hip vibe. She’s not untalented. She’s every bit as good as the Cari Ray we know today. She’s making a good living, too. Drawing good crowds. Winning over patrons one bar-chord at a time. That Cari Ray, however, is not happy. “Early on I was trying to write songs that I thought would be commercially viable and would earn airtime on the radio,” Ray explains. “I was trying to look the part and sound the part [I thought I had to play]. Lots of people offered input about how I should look, how I should sound, and how I should be. Eventually, I realized that whenever I would get ready for a gig I would undergo a huge transformation, and gradually I started to lose heart for it.”

In due time, her epiphany would strike her, and she would discover that the best version of herself is the real version of herself. She is a country girl, the product of a musically talented family and the disciple of a classically trained singer from a century before. “The woman who taught me was [in her eighties]. Her name was Lucile Reeves Horn, and she had sung in the opera-houses of Europe,” Ray says. “She married a farmer and settled in Rockville, and I remember her house was a very old, [looked like a mansion], and smelled like mothballs. She owned a baby-grand piano which she kept in a little salon-room, and we would go through our lessons. She scared me a little, but I dug her, too. I can still see her face, and I can still hear her laugh.” “[Reeves-Horn] came from a time when people sang with no amplification,” Ray adds. “So I spent the first month of voice lessons not singing. I spent a lot of those days laying on the floor with a book on my stomach learning how to breathe and then use that breath to focus and project.” A trained soprano who, at the peak of her regular practice routine, could cover a three-octave range, Ray still considers her youth in that towering, Parke County farmhouse critical to her current success. “One [lesson that sticks with me] is remembering how to breathe and focus it. The other has to do with those high notes,” Ray explains. “[Reeves-Horn] always said, ‘Imagine yourself above the note, and come down to it. Imagine that you’re already there, and you’re going to come rest on that note.’ And her other lesson was a reminder that—wherever you are—look at the back of the room and sing to them.” Ray’s past has provided her with more than her technical chops. Once she abandoned the “commercially viable” identity she had grown to loathe, she knew immediately that the persona replacing it also had to be a product of her rural upbringing. Cari Ray: “I spent most of the summers of my childhood—when I wasn’t doing chores, and things like that—running through the woods with my dog. We had 80 acres. Some of it was tillable, but much of it was wooded, and we had this winding hollow with a great shale-bottom creek [running through the middle of it]. The weeds were always high, so I would hike into the woods wearing jeans and boots, but I would carry a little pack with me that held shorts and a pair of those cheap, dime-store Keds. The [foliage] opened up at the creek bed—and it was much cooler, too, because it was low. I would put on those wading shoes, and stay down there all day. And while I was there I was telling stories in my mind and becoming different people. Often I was an explorer.” Donovan Wheeler: You explained that you come from a musical family. In what manner specifically? Ray: “On family reunions and so forth there was always a picking-party. Several of my dad’s uncles were musicians—some of them professional. One of them—Uncle Carl, who died when he was young—could play like nobody. He used to play a little for Merle Travis. When the kids were up early in the evening, everyone played gospel, but when the later hours arrived they moved more to country-blues. Of course I would beg to stay up, or I would sneak out of bed so I could listen to them.” https://youtu.be/rgrclINvV40

Wheeler: You’ve been a singer since you were very young, and you picked up the guitar in college, but tell me a little bit about your development as a songwriter. Ray: “In late grade-school and junior-high I wrote poetry. I still have one of the books from my childhood, and whenever I go over it I think: ‘Oh my gosh, this is terrible!’ But when I put it in the context of song lyrics, it’s a little less terrible. I’ve always had this drive to express myself, and once I learned to play guitar, the act of picking that up brought all of these different forms of expression together.” Wheeler: So do you think that the constraints of lyricism—the four-count rhythm and the alternating rhyme schemes—result in a sort of artistic forgiveness we don’t give to other forms of poetry or writing? Ray: “Music possesses a built-pass on having to take yourself too seriously. And because a song contains so many other elements—melody, rhythm, and so forth—different songs bring different things to the forefront. [But still] I am a lover of words. I love wordplay, and I love being clever. Sometimes that can be an Achilles heel.” Wheeler: What do you mean? Ray: “I joined one of these groups, something like a Facebook group [of songwriters]. You get an eight-week challenge where they give you a prompt, and you’re supposed to write a song based on that and then share it with the group. I did that for about three weeks and then quit because I didn’t want to write songs that way. I have no doubt that those kind of exercises improve your craft. But I feel that I hold this essential drive to tap into the commonality of human experience in a visceral kind of way and share that.” Wheeler: How is the human experience not visceral? Ray: “We move in such a tight existence, these days.” Wheeler: How do you mean? Ray: “It’s restricted. We spend so much time self-assessing and self-judging. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t take time to reflect and self-assess, but [we’re at a point now where] people refuse to give themselves permission to simply have [the experiences] that they’re having. So I feel that what I’m trying to do is be connected to my own life experience with an openness that invites other people to cut themselves some slack and do the same.” Wheeler: Some would argue that technology and social media are opening this up and allowing us to do that now in ways we couldn’t before? Do you think technology has made things more open or tighter? Ray: “Tighter. People get on Facebook and they make themselves look smart… funny… Facebook—and other social media—[functions] like the highlight reel of our lives. It takes that old ‘Keeping up with the Jones’ thing to a much deeper level, because now it’s inside yourself. Now it’s not just the Jones’ next door, it’s every single Jones you know. We look at others and say, ‘Am I as happily in love as they are?’ or ‘Why am I not traveling the world like they are?’ It’s not a real existence.” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

Wheeler: But as an independent musician you have to turn to Facebook and other social media to market yourself. Ray: “Using social media as an independent musician is an occupational hazard. Besides sharing information about gigs, I try to keep my [engagement] to the things that I see and how I see the world around me. I use photos primarily, and I try to avoid being indulgent in the process.” Wheeler: How so? Ray: “I spend a lot of time in nature, hiking and fishing mostly. When you spend that much time wading or standing around the outdoors…when you put yourself there…you happen to be there when beautiful things happen. That’s when I snap a photo, and that is my little way of trying to share it.” Wheeler: You mentioned that you worked in marketing before you switched to music. Given your musical background, how did that decision come about? Ray: “I went to college back in the ‘big music label’ days, and I knew that I didn’t look and sound a like a centerfold. So even back then I had this sense that [a music career] wasn’t going to happen for me. I asked myself, ‘If music is my thing, then what are my options?’ I can teach…but that didn’t really inspire me, or I can try my hand at music knowing that it really wasn’t in the cards. I’m also the oldest child in my family, and I was faced with that drive to be the responsible grown-up.” Needing to fill a hole in her college schedule she “got dumped into a graphic design” course and discovered both a knack for it as well as an appreciation for the artistry inherent in the field. Ray: “If you think about it, creative expression is creative expression. That’s why there are so many musicians who are also painters and writers such as Joni Mitchell, Scott Avett, John Mellencamp. Graphic design satisfied those parts of me that wanted to be responsible and successful, and also the part of me that savored a creative outlet.” Despite filling that creative need, the grind of what most of us would call normal, daily life started to wear on Ray’s spirit. In her own words she “was a consultant, doing quite well and had that American Dream thing going on. I had all this stuff which seemed perfect, yet I kept reaching for some further fulfillment which seemed to elude me.” That missing element of her life appeared when a friend asked her to pick up her guitar and join her on stage. Ray: “That experience of getting in front of a room and singing for everybody brought back all those feelings from years before [in a rush]. From then, it was a fairly short journey to realize what was missing—and not in the ‘this should be part of my life’ sense, but more along the lines of ‘this is who I should be about.’” The decision itself came quickly. The transformation into the figure she is now took a bit longer. Ray: “One of my favorite things is fire. I love to build them and watch them, but what I most love about fire is that it is simultaneously destructive and creative. Creativity is a messy experience. The path is not always clear or obvious.” The paradoxical nature of fire proves an apt metaphor for the same nature of the modern artistic experience, where the aforementioned need for creative spontaneity butts heads with the deliberate and methodical process of branding and marketing. Such a contradiction would drive any artistic purist batty. Ray, however, was past worrying about that. Having decided that her Indy-based persona would not do, she picked up her stakes, moved south to Brown County, and donned her trademark, flat-brimmed fedora.

Ray: “Something happened at the beginning of what I like to call ‘The Hat Era.’ My goal, which I set for myself when I decided that this is what I wanted to do, was to be able to make a decent living doing what I feel like I’m called to do—without a lot of attachments in terms of what that [life] looked like—whether that meant writing songs for my own performances or writing songs and pitching them to other musicians.” Ray: “I had been a hat wearer my entire adult life, so the fit was something I [intrinsically] decided was okay. When I put this hat on and look in the mirror, I look like me [as I see me]. And I made similar decisions when it came to my music. I realized that I needed to get back to the roots, country blues, and southern gospel. And when I later found delta blues and Chicago blues, I knew that was what's inside me.” Wheeler: You also mentioned that meeting and working with Reverend Peyton (of Reverend Peyton’s Big Damn Band) as a critical part of your transformation. Ray: “I’ve always been strongly influenced by the music I grew up hearing and singing, but I strayed away from letting that seep too far into my own writing for fear there was no audience for it. Rev isn’t just my producer on Swagger and our upcoming project, he and Breezy have been friends for some time. I suppose watching and celebrating the success they continue to have with the kind of music they’re making was critical in changing my mind about that. It’s not the same music I’m making now, but theirs is definitely older-sounding and rootsy [in nature]. And as I’m seeing their fan-base grow, and watching them make a living, I’m thinking, ‘Wow…maybe there IS an audience for the sort of vibe that turns me on.” Wheeler: Another part of your transformation was you decision to move out of Indy. What was it about Brown County in particular that appealed to you? Ray: “There’s so much about that [traditional, rural] lifestyle that really speaks to me: that idea of getting my hands in the dirt, fishing, helping neighbors, and all of that. Yet there was also a part of me which felt as if I didn’t quite 100% belong. I had trouble finding kindred folks who wanted to entertain the fancies of my mind. Part of the reason I moved to Brown County is because it has a lot of the things I loved as a child—as far as a way of living goes. But it’s also a little less agrarian [than Parke County], and a little more artistic. Brown County’s full of musicians, artists, hippies, nature-lovers, and earth people.” For all of the success her rebranding has brought her, it only amounts to half of the Cari Ray experience those who follow her have come to know. The other half—the addition of percussionist and vocalist Dionne Ward—would, like the rest of her catharsis, develop over time. But when they met by way of a mutual friend, both of them knew the chemistry was of the sort on which a musical powerhouse could be built. Ray: “People refer to us as an acoustic power-duo. It’s always fun when people in a bar or something come hear us from another room, then come around the corner and wonder where the band was. Once we get going, especially on the finger-style stuff that I play, we’re almost like a three-piece act. I’ll play some bass with my thumb, rhythm and melody with my fingers, and Dionne is holding down that rhythm and adding harmony.” When the pair traveled to Georgia after agreeing on a whim to compete in a battle of the bands contest hosted by Satellite Radio’s Outlaw Nation channel, the magic of the sound they had created proved its worth. Ray: “I didn’t want to drag an entire band down there, so I asked them if I could bring the duo. They scoffed and said, ‘I guess…but it’s call a battle of the bands.’ We get down there, and I look around. The next-smallest band is four-piece, and the biggest group was a 12-piece from Tallahassee. At that point I’m thinking, ‘What have I done?’ Half of them were that kind of retro-country style…people wearing skull rings and that sort of thing. I remember I turned to Dionne and said, ‘I’m sorry.’” Ward: “Cari was scared, and I said, ‘What are you talking about? We’re going to kill this thing.’ We started playing, and half the guys from the other bands stood there with their mouths open.” Ray: “When they held the finals later that night, it was us and the 12-piece.”

In the more than six years since the pair have teamed up, Ward and Ray have combined to create a sound that is not only distinctly theirs but one that feels both rural and Hoosier in nature. In short, it’s something we can claim for ourselves as well. This summer when they collaborate with Reverend Peyton on their next album, they will embrace that Midwestern Americana even further, recording their tracks with vintage equipment in the hallowed former church that is now Farm Fresh Studios (joined on select tracks by Reverend Peyton and Chuck Wills on electric and slide guitar, and John Bowyer of The Hammer & The Hatchet on mandolin). When we plunk in those newly minted CD’s and take note of the echoing reverberation that is the church itself becoming a member of the band, we will also note that none of the experience is overt. Ray and Ward hold no truck with pretention, and they have no desire to pretend to be something they’re not for the sake of scoring “cool” points. In the modern music industry you can win a quick and fickle audience by putting on airs, or you can earn sincere followers by being who you are. Ray and Ward will opt for the latter, and those of us who savor what they’re doing to the Hoosier music world will happily join them.

Wheeler proudly teaches AP Literature and AP Language to some bright and lovably obnoxious kids in a small college town. He also contributes to the craft beer website Indiana on Tap and writes for ISU's STATE Magazine. He started learning to play guitar last fall, but he remains terrible at it.[/author] Tyler Zoller lives in his hometown of New Albany, Indiana with his wife, Samantha Riggs. He is a cycling enthusiast and the owner of Tyler Zoller Photography.