Chris Trapper: Feeling Less Alone

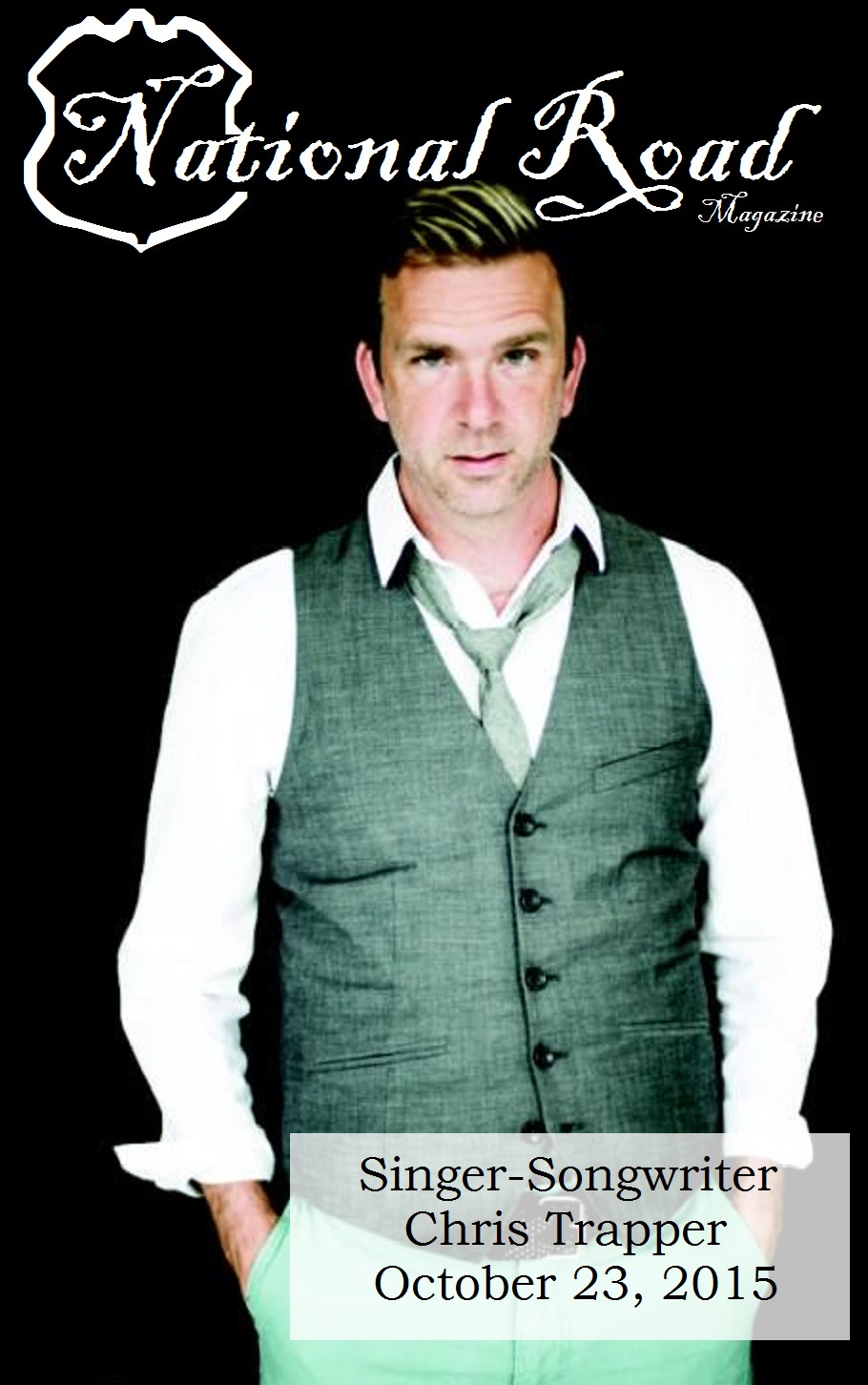

by Donovan Wheeler photos by Topher Cox

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen a man picks up his first guitar, writes his first song, and croons his first notes he presumably does so imagining himself on the big stage, under the biggest set of lights speaking to thousands (if not more) people at a time. For most of us (people such as me who never graduated beyond the middle-school, air-guitar level) these sort of “Juke Box Hero” dreams become the stuff we experience vicariously through the lives of the singer-songwriters who really do end up on those vast platforms. But at some point, even talented musicians discover that what they’re creating is most powerful when it’s intimate. When the pulpit before the masses instead becomes a lounge stage, a stool, and a microphone in front of two or three dozen respectful listeners.

A few months after I had moved past a brush with intestinal cancer—at roughly the same time that my mother was losing her own fight with the same disease—I stumbled onto Chris Trapper online, then front man for The Push Stars, singing “Keg on My Coffin.” No more than two minutes long, the song’s soulful honesty about our mutual mortality and the futility of trying live as something more than who we really are resonated powerfully with me. But the elegant lyrical simplicity of “Coffin” was hardly the only element which drew me in: Trapper’s ringing voice anchored with a stirring, acoustic melody made the song the closest thing to a religious experience I would feel. I didn’t bother to count the number of times I repeated the song, but I have no doubt that a good half-hour passed before I finally moved on to the next track on my station.

Trapper, 44, hails from Buffalo, and formed The Push Stars in the mid-90’s, at one point touring nationally with Matchbox Twenty. With his Push Stars days still on a protracted hiatus, Trapper has spent much of the last decade honing his solo work, and his recent album, Symphonies of Dirt and Dust captures all of the lyrical, acoustic, symbolic, and melodious elements which won me over when I first heard his music. As a singer and songwriter his work (and often his voice) have appeared in films ranging from There’s Something About Mary, to the final George Clooney episode of ER, to August Rush. And while the name may not be household-level, the body of work is unquestionably so. When I reached out to Trapper, he was kind enough to discuss his career with me and share his thoughts about the craft of music creation, the life of a professional musician, and how his perspective has evolved since he began almost two decades ago.

Donovan Wheeler: Let's start with the new album, Symphonies of Dirt and Dust, how would you describe this record in comparison to your past work?

Chris Trapper: I really like the way it came together, because the first few songs I was writing for [the movie Some Kind of Beautiful, starring Pierce Brosnan and Salma Hayek], so I didn't necessarily know I was writing songs for a record. I was just trying to write good songs. It's different in that I recorded it at the producer's house, not a full-on studio, so I suppose it is reflective of our musical times being changed by technology. A lot of the mix notes were sent via text, or e-mail, and everything was sent via files, and not physical CDs. As for the music itself, I think it's the most variety I've had on one album since maybe my old band's album Opening Time. It runs the gamut from French cabaret, to 90's rock, to synth pop, to Sea Shanty style folk rock. I think this too, happened organically. Rather than go in and record all at one time, I would only head to the studio a few times a month, between tour dates, so the record took over a year to make, but there was never any burnout factor.

DW: Do you see songwriting and music creation from a "creating a legacy/body of work for posterity" point-of-view? Or do you sense or see a more intrinsic motivation for the creative side of the music business?

CT: I think over the years, music for me has changed a bit, only in that it now feeds my children. I can remember in 1998, when my band had just signed with Capitol records, I was obsessed with making sure every one of my creative ideas were realized. Now I can let go much easier, but my instincts are more correct. I will know when a song is done, when nothing more can be added, when we've mixed it into oblivion....at the same time, I don't feel any less passionate than I did back then, it's just easier to get there. I think the tricky part for any musician is figuring out how to monetize their talent. It's really hard. I'd rather sit underneath the stars than be promoting on social media, but it is all part of the package.

DW: How important is the live experience, especially in smaller and more intimate venues than your time on the bigger stages?

CT: I learned years ago is that live is the only truly dependable source of income in my job. I know if I go to Philly and play a show, I'll make X-amount of dollars. Even though I now have songs used in lots of movies, and this is a continuously generating income source, it comes and goes. Up and down. Beyond the tangible, I think the live experience is everything. It is those moments of connection that make me stop, take a breath and realize how lucky I am to do this. I get to make people laugh and cry for a living, and move their hearts and minds a little sometimes too. And for me, it doesn't matter what size the venue, it is always the same goal: connection. Make people feel less alone, which in turn makes me feel less alone.

DW: I personally discovered your work on Spotify. I'm sure I've heard your tracks on one or two of the television programs in your bio, but your identity didn't resonate until I listened via Spotify. I have since followed my personal policy of purchasing your music. But all of that said: what are your opinions about the conflict streaming creates for musicians? The fact that it both promotes your work to new listeners but very likely cuts or short-hands musicians in terms of compensation?

CT: I think it's something gained/ something lost. I think it is a great time to be a FAN of music. You can stumble on a new song by an artist you've never heard of and own their whole catalog, see their wedding pictures and know where they're going to the bathroom in a matter of two minutes, all from your phone. If you had told somebody back in the 1920s, when they were doing the Charleston to a Victrola, that this would be possible, they would've asked you what planet you were from. So as a fan, I love it. As an artist, I'm skeptical, but it is usually just a matter of the businessmen and lawyers catching up to the rapidly changing technology, figuring out what money divisions are fair, and the fact is you can't please everyone. I feel like my art and commerce are all in a healthy place right now.

DW: When I first listened to you with the Push Stars I automatically assumed you were a Midwestern band. Do think I'm simply reading too much into what I'm hearing, or do you think that your work connects with Midwestern listeners for any specific reasons?

CT: I don't really know. What I know of the Midwest is pretty humble and polite, and not many American rock artists grew up more humbly than myself, or my bandmates for that matter. I grew up one of six kids in a three bedroom house. We had one bathroom for eight people, and my dad liked to take his time. My parents were drunk virtually every night of my life, but they also showed me the love of music, and the honor of being a good brother and a good son. So I suppose Buffalo, where I was born and raised, is not that far from the Midwest.

DW: What have you been able to do working solo that you often do not do (by choice or circumstances) when you're working as a member of a band?

CT: I suppose it's mostly a difference of subtlety. I was lucky to have the coolest bandmates who would let me run with ideas I was passionate about. So I didn't feel lacking with them at all, but it's the art form. A rock band has to be more bombastic, even if you are playing subdued music, your show has to have impact, or a dramatic light production, or you need a strong image. As a solo artist, the pressures are internal. What if I fuck up the show tonight? What if they don't get the jokes? What if the songs don't move them? I have no one to fall back on but myself. It's like the difference between football and boxing. If you miss a tackle in football, somebody else is often there to pick up the slack. If you miss a block in boxing, you're liable to end up on the canvas.

DW: Your list of accomplishments is extremely impressive. I know many, many musicians who would be thrilled to create the body of work you now hold. Do you feel content about where you've come since you began? Or do you feel as if something remains elusively out of reach professionally?

CT: I am happy with my work, but I want to reach more people. I am the worst self-promoter. I feel awkward telling people they should listen to me, or pay a ticket price to see me. What's so special about me? I'm just like everybody else. Get over yourself! These are the voices churning in my head. What is helping me is that I have a genuine love for people, so I am able to promote in a more personal way. Also, I have the benefit of longevity. People have heard me for the first time in movies, shopping malls, clubs, coffee shops, Spotify, but it is always different ways. A lot of artists get their one definitive big break. I haven't had that happen yet to me. My career has been slow and steady. I would like to do a little acting. I would like to have a film use my songs exclusively as the backdrop like Elliot Smith in Good Will Hunting. I don't know, I never thought I'd come this far.

DW: You seem to move easily from songs which speak to a very real, very matter-of-fact perspective on life (downcast I suppose, which is a terrible word for what I'm trying to describe) to songs filled with optimism and hope. Do you balance these moods on a consistent basis, or do you tend to work in cycles where you emphasize one over the other?

CT: This is a great question. I am a self-programmed optimist, meaning I force myself to immediately and intuitively counter a negative thought with a positive. This helps me move through life. It will be ok, I tell myself. I think this does seep into my songwriting, because I think I naturally am inclined to want to be helpful. So either I'm writing a positive song for the sake of being positive, or I'm writing something a little darker that I think people might relate to.

DW: I love to use song lyrics in my AP literature class as a springboard to traditional verse interpretation. Yet many purists argue that song lyricism and traditional print poetry are not the same. How do you feel about this? Do you see yourself, and other good songwriters, as the modern day bards?

CT: Funny you mention that because when I first started, I was playing my songs at a poetry slam in Boston. The poets were all so nice and supportive of me, telling me I would go far. I had such respect for their talent, and felt it was much harder than what I did. Some of them wrote lines that made my hair stand on end. If I needed to find a line, I could just “repeat chorus" or add a bridge. Poets don't have that luxury. I believe the less tools you can use to get a job done, while still getting the job done, the better.

DW: This one will seem odd, but... If you drink craft beer, what's your favorite?

CT: My beer of choice is LaBatt's Blue, or anything Canadian. That was a love passed down by my parents.

As Trapper wraps up the calendar year splitting his time between the West Coast and his home in the North East, he eventually returns to that home knowing that, on a listener-by-listener basis, he has accomplished what every songwriter seeks: he has connected with us, he has shared himself with us, and we have bonded with him in turn. If the goal of music is the communal experience, if the goal of the song is to link the listener to the singer…Chris Trapper has done better than accomplish it, he has embodied it.