Find Your Own Tractor

Last month I gave this address to the graduating class at Greencastle High School--the place where I have largely defined myself for over two decades. I hesitated to share this for a couple of big reasons: One, the awkward and glaring narcissism (but then I thought ¯_(ツ)_/¯...everyone thinks that of me, anyway); Two, sharing would violate the sanctity of the ceremony; Three, the message would sound hypocritical coming from me (which it does--I'm guilty of checking my phone way too often), and Four, the self-serving nature of sharing it here is a bit uncouth.

Nonetheless a handful of people have asked to read it. So I figured I'd share it with everybody. Writing is writing, and this is something I've written because...you know...it's one of those things I do. Best wishes to you all.

On a late summer day back in the early 1990’s my grandfather walked out the front door of his Freedom, Indiana farmhouse and greeted the 70-year-old man who had rolled into his driveway. The old man had changed since he last saw my Grandaddy, but he was no stranger to him. His name was “Red,” and he had driven with his family from rural Ohio. He had come to say hello and catch up on lost time. And when we’re talking about lost time, we’re talking something to the tune of 47 years. The last time the two men saw one another, they had just returned to the US after more than two years on the other side of the world, serving together in the US Army Signal Corp, in the China-Burma-India Theater of operations. After roughly 36 months running radio wire and messages from one unit to another through a jungled No-Man’s land harboring untold numbers of Japanese troops, they folded up their olive and green fatigues, strapped on their overalls, shook hands one last time, and headed to their respective homes.

What’s most telling—at least to us, anyway—is how Grandaddy lived that next half-century. It was a lifestyle I witnessed as my brother and I effectively grew up on the tiny plot of land he and my grandmother tended together. In the spring, he would climb onto his 1964 Ford 4000, drop his two-bottom plow into the earth, and travel back and forth…back and forth…back and forth—up and down each of his fields. For 16 hours a day, he would sit on top of that tractor. No air conditioned cabin. No GPS system running data analysis as he planted or sprayed. No iPod. No smartphone. The only things he had were the deafening noise of his tractor’s throttled-out engine, dust, heat, and his own thoughts.

Grandaddy’s biography has sort of become the unspoken question of modern life: What does a man do when the only thing he has to occupy his time are his own thoughts?

I have a photo collage of Grandaddy in my classroom. Most of the time it leans against the wall on the windowsill by my desk. A few of you asked me about it from time to time, but for the most part, it sits there each day largely ignored. But when my hyper-digitally connected life stresses me out—and increasingly it stresses me out more each year—I push my laptop away from my fingers, I walk up to that collection of photos, and turn my thoughts to Grandaddy.

I think of him when I turn to each of you after the bell sounds and command you to: “Switch your phones to Airplane Mode, put them away, and look at me. And if you’re not interested in what I have to say, fake it and appease my narcissism.” Many of you cooperated politely. Some of you sighed, rolled an eye or two, and surrendered to my command. But as the hour went by, I could see the signs of withdrawal on your faces. Your expressions slowly transformed, and I could see the anxiety grow in your eyes. I saw the restless fidgeting, the darting glances to those rectangular protrusions in your pockets. Maybe you felt the vibrations as your phones “blew up.” Maybe the vibration wasn’t real, just neurological phantom signals.

It’s been all too easy for people my age to point our fingers at you and say, “You need to break free of your tech addiction.” But it’s not your problem. Every soul in this room, to one degree or another lives with the consequences and implications of life in the digital age.

And for me, that price has increasingly been one I have paid in the form of less peace, less contentment, greater anxiety, and a weakened sense of self-confidence. When I put something I have written on my webpage, it’s not enough that I’ve written something that I am proud of. No. I have to then log onto my Google analytics account and track how it’s doing. If all those orange and green circles pop up on the US map, I feel the adrenaline course through me. I’m thrilled when I see someone in East Cupcake, Oregon is reading. Then I’m distraught because that person logged off after eleven seconds… I thought I wrote a great opening sentence? Why didn’t they like it?

Over the course of a single morning I’m assaulted by digital demands for my attention. School emails cascade by the hour: reminding me to “upload my artifacts on SFS” or laying out all eleven steps necessary to submit my grades. Meanwhile an email on my website account urgently begs me to drop everything and prepare for Europe’s GDPR legislation. It sounds really important. I should know what that means, but it also sounds complicated…and I’m feeling hungry. So I’ll just go eat lunch and maybe when I look at it later it will have gone away. At the same time, text messages roll in: “What’s up?” a friend asks me. “What are we making for dinner this week?” my fiancée says. “Do you have the money you owe me?” …a lot of people ask me that one. And on the same phone Facebook messages pop up: A band from Indy wants me to write a review of their new record. Another one wants me to come see their show in Fountain Square on Friday.

And it doesn’t help that, two days earlier, I made the mistake of commenting on a friend’s post about the #MeToo movement. Now I’ve got a college professor in Iowa politely dressing me down, a software engineer in Wisconsin smugly calling me stupid, and a Starbucks barista in New York saying some really mean things to me every fifteen minutes.

This is how too many of us have come to define the world we live in. We read less, but we thumb through our social media walls instinctively, skimming posts stopping only for an inflammatory meme or an “ALL CAPS” rant. We spend less time sitting on the back deck watching the trees in the horizon, but we spend plenty of time soaking in our friends’ exotic dream studying Norse literature on the southern coast of France. We spend less time in our own heads, but we lose half a day re-reading a cryptic comment, trying to get in the head of the snarky person who wrote it. We spend less time at peace with ourselves, but we spend all kinds of time measuring ourselves against a visual façade created for public consumption at the expense of the more mundane, sometimes bland, real story.

And again, when I get to that point, my thoughts trail back to Grandaddy.

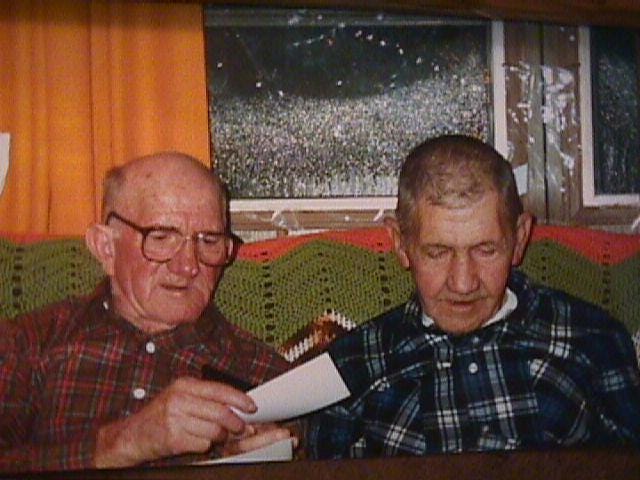

Grandaddy and Red, catching up on a half-century of lost time.

Near the end of Red’s visit, after milling about with each other’s families, Grandaddy and Red climbed into a pickup truck, shut the doors, and had a twenty minute conversation…one that both men took to their graves. In that pickup truck were all those never-shared Facebook and Instagram posts, all the emails and Snapchats. Forty-seven years’ worth of digital and instant forms of communication from which they were spared.

I’m not saying that I wish I could snap my fingers and take us back to the analog world of the 20th century…well, okay…maybe I am saying that. But I’m not naïve. I know that the digital world is here and is not going away. Technology has become the singular, existential paradox of our age: Our professional lives demand its daily use—yet a healthy mind struggles with it at every possible turn.

What I am wishing for you…what I have always wished for you…is peace. I wish for all of you to find your own respective tractors. Your own personal fields. My wish for you is that you can climb onto your seats, throttle-up, slowly work your way back and forth…back and forth…back and forth…, and live your lives happily inside your own heads.

Thank you and all my best wishes to you.

Wheeler proudly teaches AP Language to some bright and lovably obnoxious kids in a small college town. He also contributes to the craft beer website Indiana on Tap and writes for ISU's STATE Magazine. He started learning to play guitar last fall, but he remains terrible at it.