Go West, Old Man

Editorial Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed on this web site are solely those of the original authors and other contributors. These views and opinions do not necessarily represent those of National Road Magazine, the NRM staff, and/or any/all contributors to this site.

It’s just before midnight on Sunday of Memorial Day weekend and I’m looking out over the Vegas strip from my room in the Mirage Hotel. I’m supposed to be relaxing, getting away from daily anxieties, the news…reality. But looming large just on the other side of the parking lot is the Trump International Hotel, the name emblazoned across the top of the faux-gold tower. And my wife asked the front desk for a room with a view. She and the kids sleep heavily about the room. My feet hurt from walking miles of the broiling strip, my nose burns from the smoke of the casino, and my stomach aches from a Double Double (Animal Style) from the In-N-Out Burger across the street. I crawl in bed and try to get some sleep before the sun breaks over the mountains.

I have four children: three boys and a girl, ranging from a teenager to a kindergartener. It’s choir and academic bowl immediately after school, piano by 4:00, ballet by 4:30, basketball for the teenager until 5:30, more basketball for his brothers until 8:30, and that’s just Monday. Couple this wild activity schedule with the internet, social media, and our endless desire to keep up with what is constantly changing and relevant and we’ve created a culture of speed, required engagement, and constant consumption that may have already wiped out traditional ideas of what it means to experience life.

As a kid in the 80s, I’d roam suburban streets well into summer nights, cruise my bike down empty concrete creeks, and throw rocks at stop signs. We played organized sports, but not every day, and not all year long. We fished for bluegill with corn kernels, roamed the woods and new construction sites. When I moved to rural Indiana, we floated down Big Walnut on inner-tubes, cruised dusty backroads with the radio loud, and we discovered the opposite sex by actually talking to them face to face. I’m sure there are still kids doing these things today, but they are few and far between. They’ll be dancing on our ashes someday and fighting our robot over-lords, forever unfazed by a fear of missing out.

How does one combat the onslaught of activity and information? How does one slow down the machine? There are few options, but one that has been long-celebrated in American lore is the family summer vacation. And so I have legally kidnapped my family, sequestering them in the vehicles and lodging of my choice. I aim to force their worlds to slow down, even if only for brief moments. Or, all these romantic notions will fail and I’ll have to accept that I cannot thwart the changes I rebel against the most.

One of the best assets of having been to a destination before bringing your kids is you have first-hand knowledge of the place. In our case, the strip, which certainly has its obstacles and dangers, was far more kid-friendly than Fremont Street, or “Old Vegas,” to the north, where I stayed on my last trip. I don’t need to explain to my kids why the nuns on Fremont have their breasts out, or why a septuagenarian Elvis impersonator can’t walk a straight line.

Vegas and Nevada in general are a paradox. Much like an episode of Westworld, Vegas is a place where most folks from all over can come and sin without consequence beyond a hangover or an empty wallet. It’s an adult amusement park that tries to shoehorn family attractions into its menagerie of indulgences. Not fifty feet from the kid-friendly dolphin habitat at the Mirage, hidden behind a thin row of hedges sits the hotel’s clothing optional pool.

As we walk down the strip, I realize that Vegas is a physical manifestation of the digital chaos I’m trying to break free of on this trip. The endless glitz and neon and the inescapable jostling for one’s attention mimics a cluttered web page of ads and click bait. We zig-zag along the strip at dusk back to the Mirage, dodging a group of young men smoking a joint and a pack of women strutting the sidewalk in minimal coverage swim wear. As a general rule, two or three days in Vegas in enough. I can’t wait to get on with the trip. I’m ready to head out into the desert. Into the nothingness.

Vegas is a place where most folks from all over can come and sin without consequence beyond a hangover or an empty wallet. It’s an adult amusement park that tries to shoehorn family attractions into its menagerie of indulgences.

The next morning we light out for Death Valley, 150 miles west of Las Vegas. The desert is the antithesis of the city. Replacing the constant glare of signage and the ring of slot machines is a sandy void and a pervasive silence broken only by the occasional wind whipping down from the mountains, sending dust devils dancing across the flats. The sporadic desert towns are scarce and as we near Death Valley they disappear altogether, giving way to a landscape more Martian than Earth-bound. As we cross the state line into California, the thermometer on the rental car’s dashboard reads 104 degrees and I can hear nothing from the back seat. A quick turn of the neck reveals all four kids staring out into the silent sandy abyss. It is a foreboding, eerie quiet.

Entering the national park from the east reveals Zabriske Point, sitting high above the two lane highway. The thermometer climbs to 108 as I park the car. The quarter mile walk to the lookout at the top is one the most grueling short hikes I’ve ever taken and I consume an entire water bottle. The effort is worth it as we reach the peak of the paved trail, revealing a view across the entire valley floor to the range beyond, its mountains like jagged dinosaur teeth against the cloudless sky.

Death Valley is the bottom of America, sitting as low as 282 feet below sea level. Its overwhelming emptiness is hypnotic. At Bad Water Basin, the park’s (and the lower 48’s) lowest point, we head out onto the salt flats. After about 200 yards, we’re ready for the AC and another dose of water. As we load into the car, my daughter a bright shade of pink and nauseous from the heat, I’ve never been more acutely aware of the lives I hold in my hands every day.

In the car, the dash reads 114 degrees. The park demands you suffer for its beauty and the beauty is worth it. There is no wi-fi, little-to-no cell phone reception, and no sign of continual habitation beyond the ranger outposts and a singular gas station. It is a primeval land that forces you to slow down, to consider your mortality, to revel in the gorgeousness of almost nothing but a raw palate of earth tones scorched into the rock. The road through the park is either a straight line across the desert floor or a looping carnival ride of switchbacks along the mountainsides with drops measuring thousands of feet right out your car door. Lose sight of the road for a moment and you invite peril, which is the reason most fatalities in the park are not heat-related, but single vehicle accidents. And it fits my purpose well, as one glance at a screen could be my last.

Exhausted and drenched in our own sweat, we head west on highway 190, further into California. The kids begin to drift off into naps and books as the sun begins to sink and Death Valley recedes into the growing dusk of the rearview mirror. As we race the coming night, we round a blind corner at the bottom of a foothill and the Sierra Nevada loom like dark giants on the horizon, rising above the clouds they make themselves, crowns of snow sitting askance on their heads.

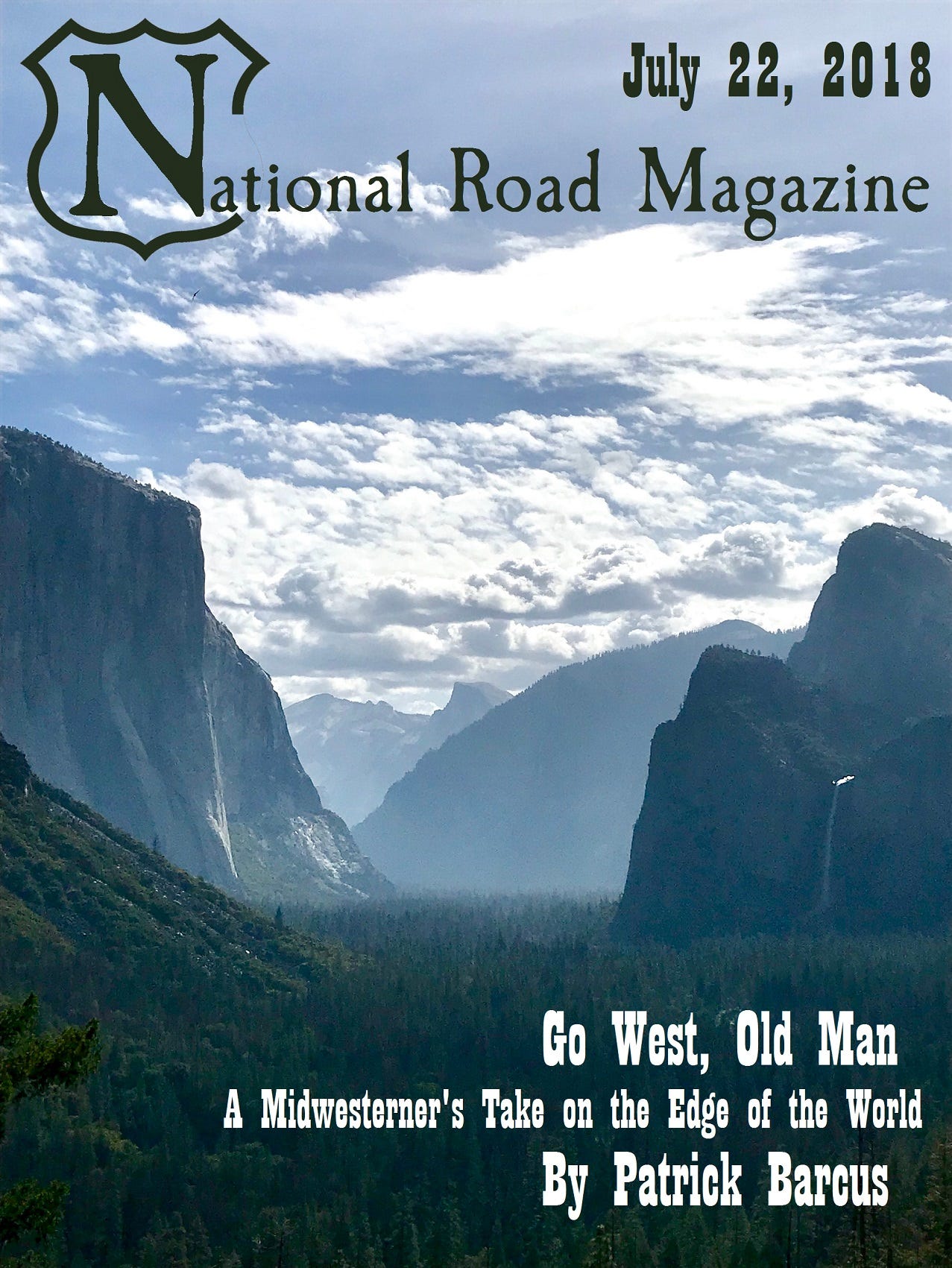

After a short overnight in a Bakersfield hotel, we start the three hour drive up the eastern slope of the Sierra to Yosemite National Park. Roughly 4 million people visit Yosemite every year and the reason is clear. It is one of the most pristine and otherworldly landscapes on Earth and the inspiration for John Muir pushing Theodore Roosevelt to create the national park system.

Our first foray into the park is a hike along the Wawona Meadows trail. Not a hundred yards into the hike I grab my 14 year old by the shoulder and pull him back, as his foot nearly lands on a six foot rattlesnake crossing the trail. We sit patiently as the snake makes its way into the brush. On our return hike, the snake appears again along the trail, slithering ahead of us. Again we let it pass with reverence.

We are strictly visitors in Yosemite. The wild owns the land and for every coyote, bear, or mountain lion we see we can rest assured several more have seen us without our knowing. The beauty of the landscape, with its soaring granite faces and misty waterfalls, can become a distraction to the real dangers of the park and we hike during the week with an ever-present vigilance. Our eyes move from trail, to scenic vista, to the dark woods, and around blind trails blocked by monolithic boulders, checking our peripheral vision for whatever might appear. We see a lone coyote jog across a meadow and mule deer, but no bears. I have been taught by my Boy Scout sons to make myself as large as possible, to shout and sound threatening if we run across a bear, but I’m convinced the only thing I’ll do is soil myself and hope the bear takes me and no one else. Thankfully, this never comes to pass.

From the lookout at Tunnel View, at the entrance to Yosemite Valley in the center of the park, a postcard world unfolds. The morning fog splits the rocky nose of El Capitan, rising 3000 feet above the valley floor. Half Dome lurks in the distance, its sheer face shorn clean by thousands of years of glacial pressure. To the right, Bridal Veil Fall cascades from a cleft in Cathedral rocks. If devoid of the tourists who surround me, I would fully expect armies of Elves, Orcs, and Men, battling over a magic ring to unfold on the meadows below. But the people are there, dangling over the edge with selfie sticks and asking others for family photos. I take a couple of wide shots of the spectacular view, knowing full well the photo won’t do it justice and continue to stare over my son’s shoulder eastward down the valley. I have never felt so small.

On a tour of the valley arranged by our hotel, we climb the steep road up to Glacier Point, 3800 feet above the valley floor. From there the world is laid bare and I feel as if I could reach out and touch the face of Half Dome, the snow-capped Sierras rising in the distance. People I consider lunatics and death-wishers dangle their legs over Overhanging Rock, which juts off the precipice of Glacier Point with nothing but thin air between them and the Merced River thousands of feet below.

As our tour bus begins its exodus from the valley, we stop at Camp 4, home to Yosemite’s oft-infamous rock climbers since the middle 20th century. Here, our driver invites a climber, preparing to scale El Capitan, on to our bus to discuss his passion. He has come all the way from New Zealand to scrape and claw his way up the face with hammer and ropes, carrying 50 pounds of gear and water up the vertical climb, which will take him two days. He’ll sleep in what is essentially a hammock nailed into the granite face halfway up, the Milky way awash above him and certain death yawning below. My children are mesmerized by this young, attractive dare devil and before I can blink a woman in front of me asks the question I have been turning over in my mind: “What does your mother think of all this?” He flashes a quick smile and responds with an answer I should have seen coming: “She doesn’t know what I’m doing until after I’ve done it, when she sees it on Facebook.”

I find a dark solace in the death of these men, who died flying through the ether while chasing life, rather than crushed by a truck on their daily commute, or having their heart give out while clicking “like” on a Facebook post.

The next day we leave Yosemite on the final leg of our trip, traversing the vast central valley of California, bound for San Francisco. As we get closer to the coast, the towns and cities rise with more frequency, culminating in the glut of cars and trucks that oozes through Oakland and Berkeley to the Bay Bridge and San Francisco beyond. I recall from an episode of Aerial America that crossing bridges is one of the greatest fears among Bay Area residents and as I sit in stand-still traffic I quickly acclimate, recalling the quake during the 1989 World Series that collapsed the upper section of the old Bay Bridge.

We’re not long in the city before the serenity of the desert and the mountains are relegated only to memories and, yes, photos in the cloud. A homeless man shouts unintelligible phrases from a wheelchair as we sit at a sidewalk café at Fisherman’s Wharf. He is quickly whisked away by police, but even after he’s gone his schizophrenic mantra still rings in my ears. I acquiesce and let the kids scramble for their screens for a brief moment to send pictures and texts to friends, or check the recent NBA finals scores. People crowd by in Golden State Warriors gear and televisions blare in every restaurant and bar crowding Jefferson Street. T-shirt shops and souvenir stands jostle for our dollars and the smell of sourdough and diesel floats on the bay breeze.

We go full tourist mode and take a Tuk-Tuk tour of the city, winding down Lombard Street, visiting Coit Tower and Golden Gate Bridge. We see more of the city in three hours than I did in three days on my last visit. As we drift past the Painted Ladies, the row of Victorian homes made famous in the opening sequence of Full House, and into the famous Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, a feeling of guilt rises up within me. Here, in the rent-controlled haven of an otherwise unaffordable city where the median house price is a million dollars, the few remaining hippies live out the Summer of Love every day. Marijuana smoke drifts out of bodegas and record stores and murals of Hendrix and skinned animals dot the buildings as patchouli-soaked bodies drift from block to block, dodging more tourists and the scythe of gentrification. We roll by, a cart full of voyeurs hell-bent on making a safari out of a slice of humanity we should be celebrating. “See the famed Hippie is his natural habitat!” They make it despite the pressures of the mainstream, despite the ridicule of squares. I lower my eyes as a hippie shouts at our driver, clearly verbalizing his frustration at our watching him. I want to get out of the cart. I want to fire up a joint and disappear into the cloud of incense and unwashed skin.

When we rise on our last day in California, the television greets us with grim news. The day after we left Yosemite, two climbers fell to their deaths while scaling El Capitan. Hundreds of miles away I am transported back to the base of the rock, my mind tracing the line of their fall. While packing, I keep the fallen climbers in my mind, reminded that the end can lurk anywhere, even in those endeavors we deem to be the ones that set us free. And I find a dark solace in the death of these men, who died flying through the ether while chasing life, rather than crushed by a truck on their daily commute, or having their heart give out while clicking “like” on a Facebook post.

Drifting south along the 101 to SFO, the city gives way to South San Francisco, filled with warehouses, modest suburban homes, and restaurant chains. It seems a sort of purgatory situated between the affluence of the city to the north and Silicon Valley to the south. The bay views appear and recede to our left as the road winds its way along the shore toward the airport.

We take off into the sunset over the Pacific and bank hard right, making a 180 degree turn to point the plane homeward. As darkness envelops the valleys and mountains below, the plane climbs. A flight attendant’s voice crackles over the intercom: “Ladies and gentlemen, it is now safe for you to use your electronic devices.” I sigh, sink into my seat, and rub my 9 year old’s curly hair as I thumb through a week of missed emails. I drift into an unsteady sleep, where I dream I’m falling from a great height, grabbing at air and broken ropes as the rocks below grow closer.

Patrick Barcus holds an MFA from Butler University and teaches writing at Indiana State University. He’s the front-man for the local band, Saturday Shoes, and also happens to be one hell of a poet.

Featured Image Credit: Alcatraz & San Francisco skyline 09 2017 6413 by Mariordo (Mario Roberto Durán Ortiz) is permitted by the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.