Holly Sims: The Decision is Yours

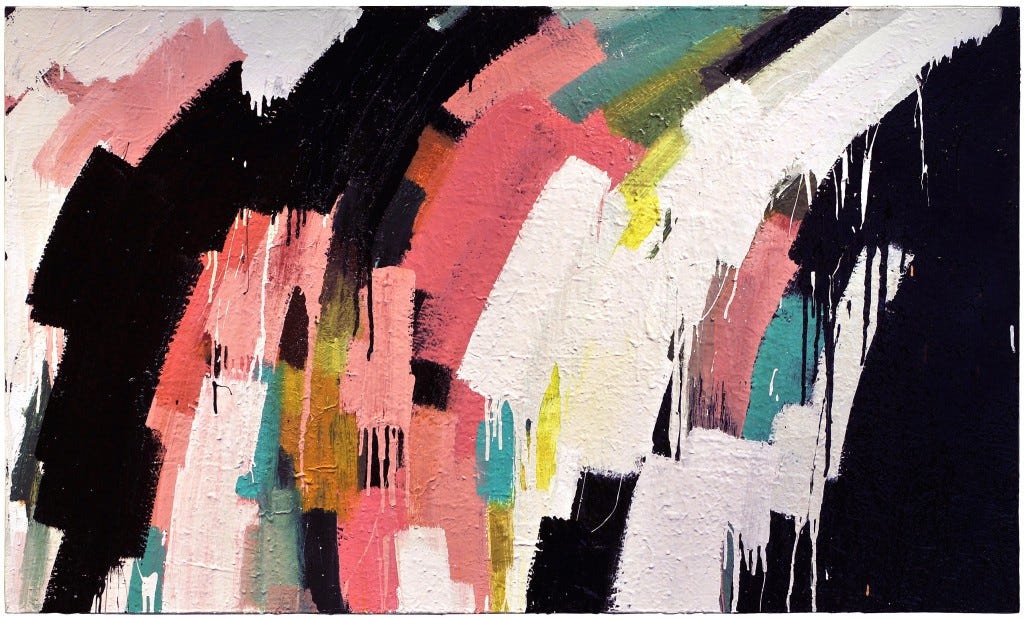

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hat goes through an artist’s mind when she runs solid blocks of contrasting colors across a five foot cut of canvas? When the end result are streaks of blacks and whites, crisscrossed by tendrils of brown, soft peach, or burnt red? We all know what the mind of a lazy thinker will determine. Having grown up in the Midwest, I’ve heard that predictable response thousands of times. And sure, maybe it is easy to pick up a brush and swipe multi-colored streaks on top of each other, but that doesn’t make the end result something we’d call “art.” Art is as much, if not more, about the process as the final product, and art is what Holly Sims has created.

But if bewildered viewers still want to question her efforts, they can go ahead because Sims won’t mind. As a matter of fact, she welcomes it.

Holly Sims: “I think just as many people won’t like it as do. They’re messy and very abstract, and I’m sure some people will look at them and think, ‘What is she doing?’ But that is what I want because there’s still a reaction. You can walk in and say, ‘I don’t like it’ or ‘Those are cool colors’ and they’re all feelings…all value judgements. And that means to me that the art is doing something for them, even if it’s not a positive or pleasant feeling.”

At the heart of Sims’ work lies something I’m only beginning to appreciate: the two-dimensional artist’s conflict between representational and non-representational form. The former would constitute most of the works we’ve seen—live, in textbooks, or on web—such as The Mona Lisa or American Gothic. The latter is where the world blurs, literally and not so as well. When I first sat down with Sims I interpreted her work as a switch from traditional, concrete-object-centered representation to its more abstract alternative. What I’ve learned, however, is that she didn’t switch, she transitioned. And she didn’t transition; she is still transitioning…and she may phase somewhere else before it’s all over…or she may work her way back to where she’s started. She doesn’t know, and she’s mostly fine with that. Despite her own directional ambiguity—or perhaps directly because of it—Sims does know that the rules she once followed are gone.

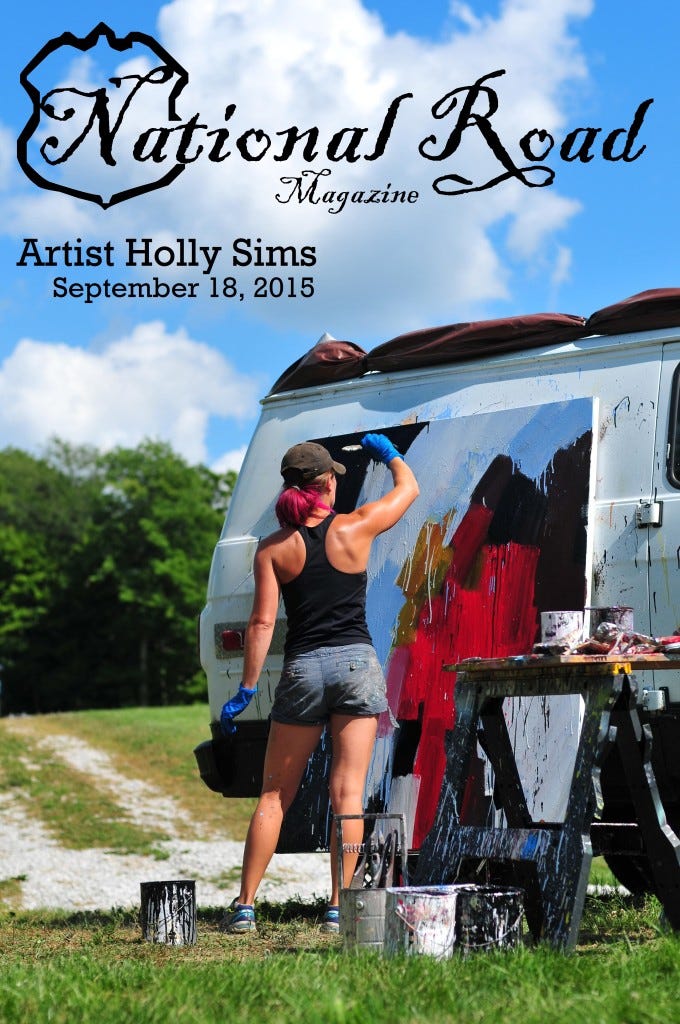

While this personal journey remains well underway, Sims took her first bold steps away from the traditional concept of art when she settled in for several days outside of Greencastle near the Boone-Hutch Cemetery. Intending to create a series of landscape vistas, Sims’ thinking evolved on that hillside, and the paintings she brought home—works which now hang in the Putnam County Museum through October—embody that epiphanic moment.

HS: “I like being outside…I’ve always painted from life. When I had a display on the square, I showed all these red chairs. I painted the chair from life; I liked the color of it, and I always felt that I have to paint what I ‘see’ because that’s what I’ve been taught.”

Donovan Wheeler: And that has changed?

HS: “It’s basically taken me two years to filter everything from grad school in order to really find myself. In school you get told so much stuff, and the game becomes this ‘Who are you?’ in the midst of all of that.”

DW: Who is anyone when they’re that young, right?

HS: “Right. In grad school I had so many different voices, so it becomes a matter of taking what has been said and figuring out what actually mattered to me out of all of that. It came down to two primary tenets…and this is what I’ve been doing in all my paintings, especially the ones I don’t show people.”

DW: Tenets? Such as?

HS: “One of my teachers in grad school, Karen Wilkins, she quoted Anthony Caro, a sculptor, who said, ‘Get rid of everything that is not the sculpture.’ And I’ve always thought that when I’m going after a painting…get rid of everything that is not the painting. When I do that, there are all these areas of color and detail which are really not what the painting is. So, if I really tell myself that, then all the actual representation disappears. I end up not interested in the objects in front of me at all. It’s all purely space.”

DW: Which takes us back to your decision by the cemetery…

HS: “Space and color are obvious things a painter is drawn to. Boone Hutch puts me up high, and I’m not enclosed. Fighting the elements…bugs sticking to the paint…and blades of grass as well…all of that can be a pain, and sometimes it makes me want to go inside. But it’s still an inspiring spot.”

DW: I want to get back to what happened on that hill, but first let’s go back to the beginning. When did art, as a way of life for you, start?

HS: “My family has videos of me when I was really small standing at my easel. Those old videos were all time-stamped, so my mom would stop recording, then start again and two hours had passed, but I was still there. But even with that, you still need somebody to tell you that you’re good, and for me that was Vicky Krider. Apart from my family, she was the first person who invested in me.”

DW: So you studied art in college I assume?

HS: Laughing. “I studied psychology at Anderson because…you know how it goes…you’re supposed to get a real job. Then, late in college, one of my professors asked me, ‘Why don’t you just be a painter?’ I was taken aback a bit because no one ever told me that was an option. So at that point I started thinking, ‘Well, maybe I could.’ So I signed on to the Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York—a summer program focusing on college-aged kids supported by the community—following my junior year. When I got there, the teachers there from the New York Studio School told me repeatedly that I would ‘fit in’ there, which was again weird to me because I’d never had anyone say anything like to me before.”

DW: Then what?

HS: “After college, I worked in Seattle as a cessation counselor, and I finally realized that ‘I just can’t do this anymore,’ so I went to a summer class called the Drawing Marathon at the New York Studio School in 2013. When I looked into it I noticed that all the teachers were my favorite artists. It was a very good fit for me, and the dean, Graham Nickson, who is a painter asked me to stay…this was all happening a month before school was supposed to start. He said, ‘You should just stay. I can let you come.’”

After her stint in New York, where Nickson served as what she called her primary influence, Sims returned to Indiana when her marriage ended and her father fell ill for the second time in a handful of years. Back home, she met her fiancée, War Radio’s Drew Cooper, and landed a couple of teaching jobs—first a temporary spot at South Putnam followed by an adjunct position with her alma mater in Anderson.

HS: “Coming back was hard, and I had a difficult time with it first. Which seems like a strange thing to say because I really like being here. I mean for one thing, in New York I couldn’t ‘just’ be a painter as I’m doing here. The cost of living here allows me that freedom, but in New York I’m working 60 hours a week plus school and art on the side.”

DW: But you did have success in New York, right?

HS: “Oh yes. I painted the mural for Anthropologie in SoHo. And when I put my work on display in New York, I sold my show…all of it. So when I came home, I had nothing and was starting clean. In New York the market for art is very high, but here the circumstances are a bit different. I would love to be able to sell some of my work, but I understand that doing so won’t be as easy as it was when I was in New York.”

DW: So when you look at your own work, who do you see in it as an influence?

HS: “Oh gosh…see? This is hard. When I look at it, it’s interesting because I see painters of the ‘50s and abstract expressionists mixed in the color. I see those mixes of color in my paintings, even though I’m not thinking about them and their work when I’m creating my own material. I don’t think that people look at my work and make instant comparisons to other painters, but I see it. I think it’s just me, probably…my own problem.”

HS: “While I’m working on a painting all I’m doing is responding to what the painting needs. Then, if it comes out looking like another artist’s work, then it just does. The reality of that is that I’m inside 50 years of, say, Jackson Pollock so many of the people painting right now are going to be gravitated to the movement he set up.”

DW: So you believe that sometimes we’re all influenced by our predecessors even if we try not to be?

HS: “I’m not like a lot of New York painters who are trying to be new and obsessing over some conceptual idea, because I don’t think the paintings have to be ‘new.’ As long as they’re true to myself…as long as what I’m putting on the canvas is honestly coming from me, then it’s okay that previous artists have influenced that. Of course their legacies are going to filter into my work…that would be natural.”

HS: “I think a lot of less-serious painters eventually lose interest in paint…the actual substance. But I’m very interested in paint and its qualities: how it drips, why it’s shiny, why it’s not. But I think serious painters really love that, and you have to keep telling yourself that it’s okay to be messy. Willem de Kooning once said that Pollock was the man who made it okay to ‘let go.’ You can see that when you move through a gallery set up chronologically. The colors are clear and crisp, the images are vivid, and then it the experimentation kicks in. I don’t want to be [Pollock], but I want to keep showing who I am which includes all the influences.”

DW: So, who is the Holly Sims we see, when we look at your work?

At this question, Sims hesitates. As soon as her eyes dart away from me and gaze blindly to the four full-suited DePauw executives sitting north of us…that’s when I know she hates it when people ask her that question. As soon as I see her forced grin and the way she shifts her weight in her chair…that’s when I know that she doesn’t want to be rude to me. And as soon as she lets out that apparently thoughtful sigh…I know that she’s tired of being polite. She wants to say to me, “Really? Didn’t we just talk about this earlier?” She’s right of course, and to her credit, she remained polite. Nonetheless, hers is a point well-taken.

HS: “I can have a feeling while I’m painting, and maybe that will come across, but I don’t think the visual experience is really about me. As long as I’m ambitious about making the painting, I don’t see how there can any non-response in return. If I were going into a work with an outcome in mind, then I think it closes all the other doors, both for me as I’m creating it, and for viewers who later take it in. These paintings are not self-portraits. They’re not about Holly at all, but it’s all about making a mark—a physical mark on the canvas—and then responding to that mark with another one…or with color. Now I have two marks on the surface I have to respond to. When you approach it that way, it becomes too natural to be scripted or pre-designed. What you’re making is a thing in itself.”

DW: And what’s your sense about how viewers respond to it?

HS: Here she smiles again, this time without condition. “One man—your typical farmer—approached me, looked at my painting, and said: ‘You know, I think you need a dog or a cat in there.’ And I’m thinking, ‘Okay, okay…’ But then he comes back on another day, and this time he says, ‘You know actually, I was thinking…I think there needs to be some red in that painting.’ After he said that, I stepped back from it and agreed with him. But the best part of it is that it was a response. Here’s an older gentleman, with no history interacting with abstract art, and he reacted to it. Other people have approached me and told me that they love seeing me doing my work out there, but that meeting with the old farmer…that was my favorite moment [at Boone Hutch].”

While looking at her samples, Holly put the onus of reaction on me, just as she wants it for everyone. What did I think? At the time, I hemmed, hedged, and generally avoided a direct comment, mostly because I wasn’t ready. But when I walked the aisle at the museum, no fewer than four trips the length and back, I had my answer…which started with this question: Of all her pieces on display, which one would I want to hang in my house? And why?

My answer is “Number 6,” a horizontal piece bordered by black slashes, split by a streak of dripping white—the two extreme tones appearing to wrestle with one another for control of the canvas. Caught in the melee were the earth tones: tiny smidges of greens peeking from behind protruding globs of reddish pink. So much black-and-white fighting for the space, but my eyes turned to the fragile nature of the much smaller, but more vibrant colors. The beauty, the warmth which those little bits of green evoked…that’s all we really want. We live for that, yet we’re consumed most of the time by the ideological, economic, political, and generally mercurial forces which never let us go.

While Gus Moon’s voice rang through the back of the museum, while patrons nibbled on cheese cubes, I noticed a much older, more traditional landscape playing the role of the wallflower to the evening’s showcase. Robert Kingsley’s Sycamore Pasture looked to me like the kind of painting which Holly Sims had originally set out to create. The serene balance of earth and sky, and of green and bark, all resonated with me for the same reasons as Sims’ little splotches of hope on her canvas. The difference was the urgency. In her remarks on the night of her show’s opening, Sims said that her work underscores “the loss of control in making yourself available to the totality of the work.” Kingley’s painting showed me the world we all wish we could have, but Sims’ work showed me the world we have to make do with.

This is hardly a novel interpretation. We can all sense the tension filling up every bit of empty space in our society, even a passing farmer looking at a painting he doesn’t fully understand, but somehow knowing it needs a little red.