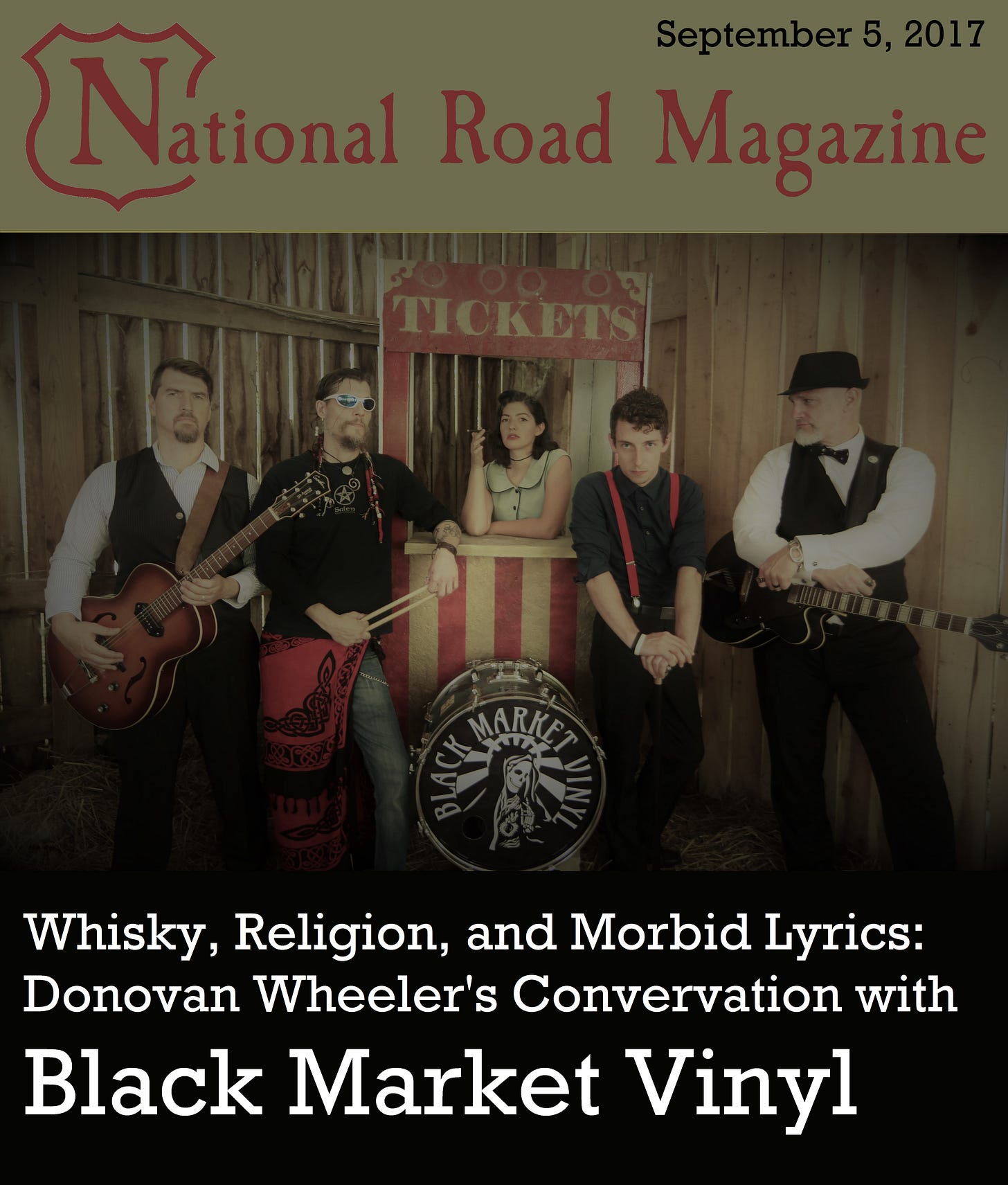

Music, Religion, and Bourbon: A Chat with Black Market Vinyl

Mixing a range of sounds including heavy-metal, early rock, classic rock, blues, and more... Bulwarked by sound, technical control... Arrayed with a triumvirate of hypnotic lead vocalists... Loaded with buckets of visual style... Black Market Vinyl is poised to become western Indiana's next "must see" for the region's local music patrons.

by Donovan Wheeler featured image by Sarah Rees additional photos by Bobby Laney

[dropcap]U[/dropcap]nder the thick foliage of a late June evening, Matt Rees’ sunroom sits along the edge of the small clearing that serves as his back yard. It’s a cozy place—small and narrow. Packed bookshelves run along one side, and windows to the outlying woods blanket the other. Taking up most of the space is the enormous coffee table, littered with candles, eclectic odds-and-ends, and bourbon…lots of bourbon. It’s a room that evokes a sort of Narnian wonder: a place where you could find your 75-year-old grandmother crocheting your sister’s afghan, or the place where your wizened grandfather sits cross-legged in a button-down cardigan reading Nietzsche, or the hangout where a rock-and-roll band throws down goblet-shots of Knob’s Creek an hour before rehearsal. In other words, it’s cool. Here, all five members of Black Market Vinyl gather. And when we talk about “Black Market Vinyl” what we’re really talking about is family. There’s Rees himself, the band’s defacto front man and founder. His younger brother, Shem sits at the drums, and his brother-in-law Joel Ruff works the guitar. On the bass is Will Ripperger, dating daughter Jamaica and the father of Rees’ grandchild. And in the middle of it all, twirling and half-pirouetting with tambourine in hand is Rees’ other daughter Wednesday, the band’s vocal and visual anchor. Ruff—the towering lead guitarist who often owns the stage with his style alone: dapper ballroom dance shoes, a jazz-age power fedora, and a white shirt/dark blazer combination—commands center-stage in the sofa under the windows. Beside him, starkly and stylistically contrasting Ruff’s zoot-suit scene, Shem sports a series of tightly wound dreadlocks which dangle from his scalp, resting on his shoulders. Behind the distinct rims of his glasses, and under the comforting glow of his casual grin, is the paradoxical mind of a man who has seen a lot of shit go down…and who takes very little shit from anyone who tries to dish it out. [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] [box type="info" align="" class="" width=""]Black Market Vinyl - First Album Release: September - Shows: October 7th @ The Lafayette Theater, October 29th @IMA Beer Garden Closing Party, December 5th @ Greencastle Music on the Square[/box] [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] To Shem’s right, young Ripperger straddles a small kitchen chair, accentuating his friendly yet sheepish grin with a frequent series of subtle head-nods. Not far past him Wednesday sits bearing the polite, demure smile of someone too humble to embrace her genius. And just past my seat, at the “head of the table” in a manner of speaking, Matt Rees pours himself a shot of Knobs. Behind him, the side-one vinyl he laid on the turntable warbles the crooning echoes of Howlin’ Wolf casting a soft ambient jazz which wafts over the evening’s conversation. You could argue that the origins of the band lay deep in the folds of time, when a very young Matt Rees and an even younger Shem latched onto their first musical instruments and almost immediately began creating their own sound. But from a more pragmatic sense, Black Market Vinyl was born a few dozen feet from where we sat. Out there, in Rees’ back yard, next to the embers of the campfire, the music began. “We would hang out around the fire,” Rees explains. “Shem would bring drums, and Joel would say, ‘How come nobody’s bringing a guitar?’ Pretty soon we were playing songs. Then we started writing songs, and not long after that we started thinking about forming a band.” In short order they signed on Ripperger, and with a four-man complement, they felt they had their group. But that was the summer Wednesday came home from college, and sitting among the boys, the powers of persuasion did its work. “We coaxed her into singing by the fire,” Ruff says. “At first she wouldn’t sing for us.” “She said, ‘I’ll do your background,’ but man…everything popped when she started singing,” Matt Rees adds. “And then she started writing her own songs which forced her to take lead.” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

“Matt had gotten a guitar and four-track. He was in his room doing shit with his headphones all the time, and I was thinking, ‘What is going on?’ Then he played me something, and I thought ‘I want to be involved in this, but I don’t want him to be able to tell me how to do it.’" Shem Rees

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] [dropcap]F[/dropcap]rom that genesis, the band found its voice and in most respects its visual identity as well. Mixing a range of sounds drawing from heavy metal, early rock, classic rock, blues, and more; bulwarked by sound technical skills; arrayed with the triumvirate lead vocal stewardship of Rees, Wednesday, and Ruff; and buoyed by the aesthetic on-stage style of five distinctly flamboyant personalities, Black Market Vinyl is quickly becoming western Indiana’s secret weapon in the music scene. Donovan Wheeler: So how did you guys find yourself interested in music? Matt Rees: “[Shem and I] been playing since we were young…about age 12. We were lucky enough that each of us picked a different instrument.” Shem: “Matt had gotten a guitar and four-track. He was in his room doing shit with his headphones all the time, and I was thinking, ‘What is going on?’ Then he played me something, and I thought ‘I want to be involved in this, but I don’t want him to be able to tell me how to do it.’ We’ve always created. I’ve probably played something like three cover tunes in my entire life, because all the bands I’ve been in were creating new stuff.” DW: So you prefer the original sound to any cover work? Shem: “I go to open mics, and there’s a drum set, and they want to play Tom Petty. That feels really stale and unborn to me. That’s because me and Matt have created since day-one, so [cover music] is fish that I have never fished for.” DW [to Joel Ruff]: What about you? You grew up in Japan while your parents performed missionary work. How did you find your way to music? Joel Ruff: “My dad was a ‘folkie,’ and he always had guitars around the house. He was trying to get my sister to play, and when they weren’t around I would pick one up and play it. I didn’t have the traditional high school experience, so music was my window to the world. I listened to Bob Dylan, Hank Williams, and a lot of other stuff that’s not cool to listen to in high school.” DW: What does life as the son of missionary workers do to a young man’s perspective on the world? Joel: “It makes you more rebellious, but it also gives you an appreciation for [religion] as well. I would be the first to speak out against it with one crowd, but with another I would be the first to defend it. It creates a different viewpoint which ekes out of my lyrics quite a bit. They’re pretty much speaking about murder or religion…not a lot of love songs.” DW [to Wednesday]: You’ve been writing several songs for the band as well. Do you write a lot about murder and religion? Wedensday Rees: “I came up with a melody for a song titled ‘Monster,’ but I didn’t know what I wanted to write around it. And Will had once said that the scariest things in the world are people…humans, and that’s what I allude to in the song.” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] [dropcap]M[/dropcap]uch like her father, Wednesday first picked up the music bug as a middle-schooler. Unlike her father, she dabbled in the complex chord arrangements from Beatles tunes, and eventually she mastered the much more tricky and challenging fretwork. Still, despite her father’s claim as one of the best guitarists in the band, she almost never hefts a six-string when she’s on stage. From her own recollection, she’s picked up a guitar a grand total of one time. Regardless, her presence on stage draws the crowd away from its collective smartphone browsing or the shouted conversations which often render a band’s efforts into little more than ambient, electric elevator music. Those simple, subtle, soft gyroscopic rotations and that effortless flit of the tambourine work with the Zoot-Suit Noir coming from the rest of the band, making the visual ensemble reason enough to show up for beers in the first place. Joel: “She’s like our Stevie Nicks. When you think of Fleetwood Mac, you never think of Lindsey Buckingham, even though he’s a technical genius. People always think of Stevie, because she has a unique look and unique sound. And that’s great. The singing is great, and the music is great. So we can be the old men in the background. We don’t really care.” DW: You guys have had experience in metal bands before this. How has your transition to this new sound been for you, given your previous experiences? Matt: “The metal scene is very collaborative. You wouldn’t think so. You would think it would be a bunch of tough, mean guys, but they’re super nice people. And nobody wants to listen to a band for two hours. They want to hear a group for a half-hour or 45 minutes. So when you put a show together you get three or four bands that way the sound is always changing…because it’s all going to give you a headache anyway. But in this genre it seems like everyone wants to grab it all for themselves, and it seems like the venue owners just want to pay for one band, and they want them to fill up all the time. So it’s a lot less collaborative. The irony of course is that there’s only a couple places to play metal, but there are so many more places to play for the music we’re doing now, between the breweries and all these little pubs and stuff…there’s a billion places to play. But breaking into those places has proven difficult.” Joel: “Indiana is also not the best place for original music. Everything is cover bands. Everyone wants to hear ‘Celebration’ or Mellencamp.” Shem: “It’s like being tied to the whipping post. I’m not fucking doing it.” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] [dropcap]F[/dropcap]rustrations aside, the Hoosier music scene plods on. It evolves, and stands today as a scene which is improving. All the bandmates admit that the growth of events such as Indy’s Virginia Avenue Folk Fest (expanding from one to five days for next spring’s event) are signs that Hoosier music lovers are tuning into the unique and the original. For Rees and company, such changes can’t come soon enough. In Rees’ perfect world, audiences who maybe don’t like the first band they see will hang around by the bar because the next band…a different act altogether…awaits them in another 30 minutes. DW: Like almost all the bands I talk to, everybody holds day jobs. Everyone has real lives which extend so far beyond music. So why do it? Why put yourselves through all of this when you already have very demanding, very normal lives outside of this? Will Ripperger: “I find a lot of fulfillment playing when I’m alone at home, but it’s such great fun playing a show for somebody. And that’s really what it’s about for me. It’s fun. I’m going out there, and I want to have a great time and create an atmosphere. And the thing I love the most about playing bass is that, if I’ve done everything correctly, then I’ve done nothing at all.” DW: But you do draw some attention with your enthusiastic movements as you play. Will: “Yeah…with my ‘balterning’?” Shem: “I don’t even know what that word means, dude.” Will: “Baltering means to dance without any training or artistic influence.” Joel: “You’re a good foil to Wednesday’s dancing.” Matt: “You’re not self-conscious about it which makes watching you guys a lot of fun. I turn to my side and think, ‘There’s a lot of shit going on over on that side of the stage.’” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

"Preacher's Son" by Black Market Vinyl

http://nationalroadmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Preachers-Son-for-mag-article.mp3 [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] DW: You have mentioned before that, once you decided to make this band happen, you needed to create a long set-list of original songs. How do you wire your brain to crank out that many songs on a level and scale of that magnitude? Matt: “Joel writes constantly. He shows up all time saying, ‘I’ve got three new songs!’ Well…that’s great. Now we have 20 that we haven’t recorded. His brain works constantly, that’s all he does. And I write as well, Wednesday writes, and Will is getting close.” DW: What happens when that individual songwriting experience reaches the band as whole? Joel: “Some stay pretty close to the original vision. We’ll come in and say, ‘This is how this song is.’ But other times it’s just doodling around. Because I write lyrics all the time. I don’t write songs, per se. So Matt will add chords and melody, Will adds baselines, and that sort of thing.” Matt: “My favorite thing is to write a song and say, ‘Hey, Joel, can you play it?’ Because he never plays it the way I did, and then it takes on this fresh new sound. That’s when the process gets exciting for me.” Joel: “What’s interesting is how you can work and work and work to get a song just right, and you never feel great about it, but then another idea hits you in the car and a great song comes together without any work at all.” Matt: “My recording app is the first one on my phone for that very reason. I’m in the car all the time humming bits of ideas into it. And Joel is someone who can take a set of words in a quiet room and say, ‘The song needs to sound like this.’ Then we’ll work it out until we get it right. I’m the other way around: I need to figure out the music first, and then I’ll write the lyrics into it.” DW [To Wednesday]: How does the process work for you? Wednesday: “It’s really hard for me to write songs unless I’m really into the lyrics and the chords I’ve chosen. So as long as it feels right and I can go with it, then the ‘content’ doesn’t necessarily matter. I just wrote a song about a guy I passed in Colorado. I know nothing about him in real life. I just looked at him, made up a story about him, and turned it into a song.” DW: Regarding your musical composition: do you find making original melodies, chords, and so forth easy, or does is that a challenge? Joel: “Well…first of all, there’s nothing that’s new. Music used to be collaborative. ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ was Carl Perkins’ song. A huge hit. But then he gave it to Elvis, and ‘boom!’ Now no one thinks of Carl Perkins anymore. But they shared. So when you’re writing, you don’t want to sound like…Tom Petty…[the room fills with laughter]…so you can change it around, but there’s nothing out there that’s ‘original.’” Matt: “There are people who strive for originality, and those bands are cool. We are not that band. If we have any appeal at all, it’s that we sound familiar, but we don’t sound like we’re copying anybody…at least in my head.” [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] [dropcap]D[/dropcap]espite Rees’ modest claims, Black Market Vinyl casts a distinct aura of originality. Be it the suave, Jazz Age visual aesthetic accented by Ruff’s dominant frame; the rhythmic, on-stage gravitas punctuated by the movements of Wednesday and her brother-in-law Ripperger; or the haunting father-and-daughter vocal combination echoing from center stage, the band’s a product of myriad influences. No doubt Rees’, Ruff’s, and Shem’s long-standing work with heavy-metal bleeds into BMV’s rock counts—especially the hard counts. But a personal turning point hit Matt Rees when he used to haunt Tavia Pigg’s long defunct establishment in Greencastle. Matt: “She had a place which was part art gallery, pub, steakhouse…she had everything. I used to go in there—she was displaying my art at the time—and she played this amazing music. I asked her, ‘Who is this?’ It was the Squirrel Nut Zippers. I fell hard for this band. Became a huge fan and collected all their music—and it was hard to find vinyl in the ‘90’s. That was my biggest influence by far. Pokey Lafarge was big for me, and Joel discovered C.W. Stoneking.” Joel: “It’s a mixture of blues, and old country, and folk…the good stuff.” DW: I want to go back one more time your roots as metal musicians. Given the near impossibility to tie modern bands—especially local and regional bands—to specific genres, does that free you up to incorporate your metal past into your new sound? Matt: “Well, [pointing to Shem] if you want someone to thump that double-bass…” Shem: “I think the reason is because when I face new music, I don’t know where they’re coming from. So I’m thinking, ‘I’ve got to play metal but dumb it down.’ I don’t mean that as an insult. What I mean is that there’s not a much going on with my hands. So I slow it all down and it becomes Black Market Vinyl. It becomes its own thing.” [dropcap]I[/dropcap]ts own thing. When Rees occasionally cross-references Black Market Vinyl with other bands (often seeking similar acts he can pair up with in gigs), what he finds is that very few out there sound like them. And certainly no bands in western Indiana wrap a paradoxical veneer of bippity-bop (sometimes sounding like a Stray Cats set) around a core of morbid lyricism hearkening to bands such as The Cure. Let’s face it, even when we finally learn what we’re tapping our feet to when Paul Simon sings “Mother and Child Reunion,” we keep tapping anyway. The experience is no different when we pleasantly bob our heads and shoulders to Vinyl’s “Love is a Dog from Hell.” Slap whatever label you want to on that. The label Joel Ruff uses is called “rock and roll.” Shem’s inclined to call it “fucking great!” So long as it moves you, mentally and rhythmically, then you can call it the only thing you need to: you can call it good. [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]

[divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"] [author title="About Donovan Wheeler" image="https://scontent-ort2-1.xx.fbcdn.net/v/t1.0-9/20245425_10209586011222255_5635163012302497974_n.jpg?oh=6a9ea45d73bd44763c9a703c0e8f1e45&oe=5A246C91"]Besides founding National Road Magazine, Wheeler writes for several other publications and teaches high school English to a group of lovably obnoxious teenagers. He doesn't play much golf anymore (it makes him too angry), but he loves playing with his guitar (he only know two chords).[/author] [divider style="solid" top="20" bottom="20"]