My Spotify Dilemma: The Price We Pay for Free Music?

In 1986, I went to the College Mall in Bloomington with my younger brother. It was a Friday or Saturday night, and I bought the album I’d had my eye on for several months: Mike + The Mechanics’ self-titled debut album featuring its catchy “80s-esque” premiere track, “All I Need is a Miracle.” Of course when I say that I “bought the album” what I mean is that I actually bought the 80s equivalent of the iPod…the cassette tape. Loaded with synthesized keyboard work and those now-bizarre digi-drums which poisoned most of the best of the decade “Miracle” became one of those tunes I played over and over on my clunky GE knock-off of the Sony Walkman. When the mood struck me, I could sometimes make it all the way through “Silent Running,” the song preceding “Miracle” on side one. But most of the time I was not willing to sit through the laborious pacing of “Running,” so I’d go through what every cassette owner had to endure to get to my favorite song: hit fast-forward. Working through a cassette tape often required an internal ability to measure time down to the second and an innate ability to listen to the rhythms of the spools and they wound up those ribbons of black, magnetic plastic. Many times, I stopped moments before “Running” ended; other times I caught “Miracle” during the opening bars. But too often I was never close: FF…STOP…PLAY… “Nope!” FF…STOP…PLAY… “Too far!” REW…STOP…PLAY… “Damn! Too far the other way.” FF... Eventually, because the laws of both physics and attention demanded it, I surrendered and started listening to the entire album…I mean cassette tape. The evolution of music delivery in the years which followed: the Compact Disc, iTunes, and the iPod all changed the dynamics of song-hunting in rapid order, but nothing has transformed listening to music as much as the advent of streaming services. I have to admit, if something like Spotify had arrived when I was a kid, I would have salivated over it. As a middle-aged adult, I do that now. But Spotify—and its competitive precursor Pandora—hasn’t just changed how I listen to my music, it’s actually changed what I listen to as well.

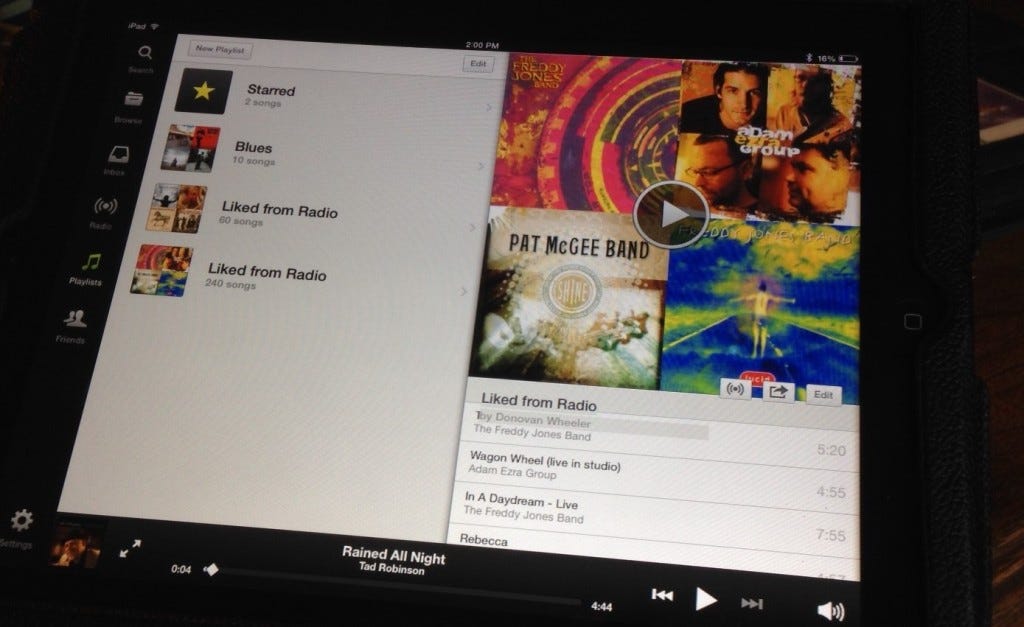

That happened roughly two summers ago. While driving home from Avon, I listened to a clever and inventive track on WTTS, one with two astounding guitar riffs: The Freddy Jones Band’s “In a Daydream.” Desperate to hear the tune again, I tuned into my recently established streaming account and discovered that this band—which I had never heard of—had recorded a plethora of great songs ranging from “Waitress” to “Old Angels” to one of my favorites, “Contender.” As I delved more deeply into the mystique of Freddy Jones (a band in name only, functioning as little more than an empty agnomen), Spotify’s then-effective radio algorithm led me to dozens of other talented acts…also groups I’d not known about. Jackopierce, The Benjy Davis Project, The Virginia Coalition, the Native-American blues act Indigenous, Red Wanting Blue, Bob Schneider, nelo (intentionally lower-cased), The Alternate Routes, and gads of other bands suddenly flooded my listening time. Quite instantly, I set my aging iPod aside and turned away from my now-embarrassing 80’s playlist, and I got so caught up in my newfound music world that I even stopped listening to The Beatles for several months, returning to them only when a wave of begrudging obligation compelled it of me. And a year later, when Spotify opened up access and allowed me to go to any album, listen to any song, without the burden of skip-limits or randomization…I officially thought I’d arrived in Wonderland.

Like Lewis Carrol’s classic, however, this world full of enchantment harbored a darker underbelly. Because my phone data was limited, I opted to take my growing list of favorites on Spotify, buy them on iTunes, download them to my iPod all so that I could enjoy them when I was on the road. Doing so spared me the irritation of yet another Home Depot ad as well as Spotify’s suggestion that I might really dig the sounds of the Latin music sensation Gloria Trevi…whoever she is. It also eased that nagging sense I that was somehow stealing the music. I had grown up in world where nothing was free, not even lunch as I had been told thousands of times as a kid. And while Spotify did throw out those repetitive and poorly market-researched commercial spots every hour or so, I sensed from almost the first day I listened to it that the musicians and songwriters weren’t getting the same deal they’d gotten from conventional, over-the-airwave radio play. My hunch was right. As songwriter Van Dyke Parks details in an editorial penned over a year ago, free music comes at a significant price. In the column Parks notes that a song which once would have bought him a house with a swimming pool now garners him little more than a nice meal or two at a fancy restaurant. Plenty of hard-working, ditch-digging types—resentful of the opulent success the world hands people who sit at desk—might be thinking that a turn of luck like this amounts to an “about time” moment. But any half-witted economics student knows that when the value of labor is shattered, the quality erodes quickly. That terrible service at Walmart…? That’s what $9 an hour will get you.

Granted, for young unknowns, Spotify and the Internet in general has proven revolutionary, crippling the power the once titanic record labels (hence my previous implicit statements about lousy 80’s music). Local singer Carly Rhine told me when I spoke to her that she was willing to live with the $0.00065 per play that Spotify hands over because her top priority is “getting my music out there.” And therein lies my dilemma. As a fledgling freelance writer starting up this magazine, I can appreciate the measured urgency young artists like Rhine feel as they struggle to break out of the haze flooding the web. Like every other writer, I would love to charge a “price per issue” for my work, but if I do that in an already crowded Internet where I can read SLATE, SALON, TIME, and MOTHER JONES for free my steadily growing readership numbers would plummet. But I also sympathize with Parks, and even more intimately with musicians I know such as Tad Robinson who spoke to me about his flat-lining royalty revenues which he had once expected to grow. And the larger question singer-songwriters such as Robinson raise are more disconcerting: what kind of music are we going to listen to when the only people who make it are doing it for free? Somewhere, in some other string-theory strand of a dimension, all the world is listening to highest quality music, produced and shared at no cost. In another strand, everyone is listening to the highest quality music for a price: be it in the form of album prices or fair and frequent advertising rates. And in still one more universe, everyone is listening to a garbled cacophony of hootin’ and tootin’…most of it is awful, and finding the good music takes patience and work. Right now we live somewhere among the three, but the music we are enjoying in this is “golden age” of Internet radio is destined to shift towards one of the those options before us. And in two of them, somebody loses big.